Even to a high-flying bird this was a country to be passed over quickly. It was burned and brown, littered with fragments of rock, whether vast or small, as if the refuse were tossed here after the making of the world. A passing shower drenched the bald knobs of a range of granite hills and the slant morning sun set the wet rocks aflame with light. In a short time the hills lost their halo and resumed their brown. The moisture evaporated. The sun rose higher and looked sternly across the desert as if he searched for any remaining life which still struggled for existence under his burning course.

And he found life. Hardy cattle moved singly or in small groups and browsed on the withered bunch grass. Summer scorched them, winter humped their backs with cold and arched up their bellies with famine, but they were a breed schooled through generations for this fight against nature. In this junk-shop of the world, rattlesnakes were rulers of the soil. Overhead the buzzards, ominous black specks pendant against the white-hot sky, ruled the air.

It seemed impossible that human beings could live in this rock- wilderness. If so, they must be to other men what the lean, hardy cattle of the hills are to the corn-fed stabled beeves of the States.

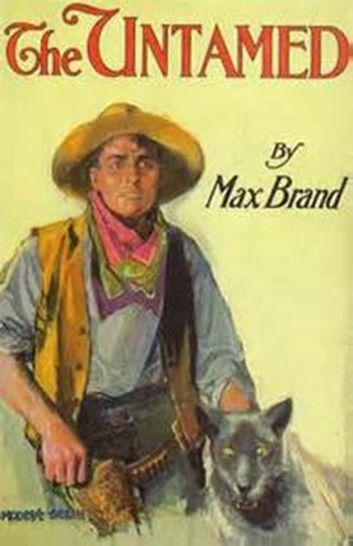

Over the shoulder of a hill came a whistling which might have been attributed to the wind, had not this day been deathly calm. It was fit music for such a scene, for it seemed neither of heaven nor earth, but the soul of the great god Pan come back to earth to charm those nameless rocks with his wild, sweet piping. It changed to harmonious phrases loosely connected. Such might be the exultant improvisations of a master violinist.

A great wolf, or a dog as tall and rough coated as a wolf, trotted around the hillside. He paused with one foot lifted and lolling, crimson tongue, as he scanned the distance and then turned to look back in the direction from which he had come. The weird music changed to whistled notes as liquid as a flute. The sound drew closer. A horseman rode out on the shoulder and checked his mount. One could not choose him at first glance as a type of those who fight nature in a region where the thermometer moves through a scale of a hundred and sixty degrees in the year to an accompaniment of cold-stabbing winds and sweltering suns. A thin, handsome face with large brown eyes and black hair, a body tall but rather slenderly made—he might have been a descendant of some ancient family of Norman nobility; but could such proud gentry be found riding the desert in a tall-crowned sombrero with s on his legs and a red bandana handkerchief knotted around his throat? That first glance made the rider seem strangely out of place in such surroundings. One might even smile at the contrast, but at the second glance the smile would fade, and at the third, it would be replaced with a stare of interest. It was impossible to tell why one respected this man, but after a time there grew a suspicion of unknown strength in this lone rider, strength like that of a machine which is stopped but only needs a spark of fire to plunge it into irresistible action. Strangely enough, the youthful figure seemed in tune with that region of mighty distances, with that white, cruel sun, with that bird of prey hovering high, high in the air.