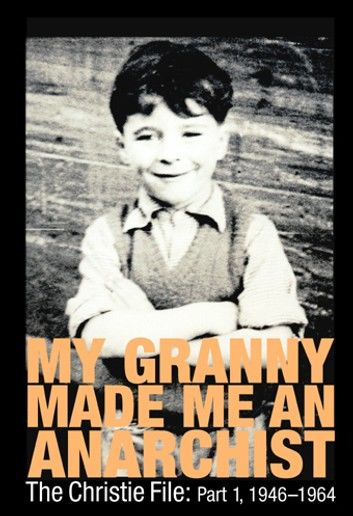

“Stuart Christie's granny might well disagree, given the chance, but her qualities of honesty and self-respect in a hard life were part of his development from flash Glaswegian teenager — the haircut at 15 is terrific — to the 18-year old who sets off to Spain at the end of the book as part of a plan to assassinate the Spanish dictator Franco. In the meanwhile we get a vivid picture of 1950s and early 1960s Glasgow, its cinemas, coffee bars and dance halls as well as the politics of the city, a politics informed by a whole tradition of Scottish radicalism. Not just Glasgow, because Stuart was all over Scotland living with different parts of his family, and in these chapters of the book there is a lyrical tone to the writing amplified by a sense of history of each different place. When we reach the 1960s we get a flavour of that explosion of working class creativity and talent that marked the time, as well as the real fear of nuclear war and the bold tactics used against nuclear weapons bases. It is through this period of cultural shake-up that Stuart clambers through the obstructive wreckage of labour and Bolshevik politics, and finds a still extant politics of libertarian communism that better fitted the mood of those times. Now, in 2002,it is Stuart who finds himself quoted in an Earth First pamphlet as the new generation of activists for Global Justice by-pass the dead hand of Trotskyist parties and renew the libertarian tradition.” John Barker

“What exactly Stuart Christie's Granny is being made responsible for is rather a lot. Given that the opening scene of this riveting autobiography is a bitterly funny account of his trial for attempting to murder General Franco, it seems that the poor lady is being saddled with more responsibility than is fair. Moreover, her quick-draw way with a bar of carbolic soap when confronted with obscenity does not mark her out as much of a subversive. On the other hand, as I know only too well from my own experience, Grannies, like Stuart’s, can provide an ethical framework that leads to serious questioning of conventional politics. As this marvelously readable and often moving book reveals, the real responsibility lies in part with the post-1945 break-up of a social system based on deference — although it would be interesting to know why it did not have the same effect on Alex Ferguson. Forged in the spirit of community in poor working-class Glasgow, profoundly influenced by Chic Murray and Dennis the Menace, local religious conflict, the father who went out for a packet of fags and did not come back for twenty years, Christie’s road to a Francoist courtroom in Madrid had many by-ways. Perhaps the profoundest influence of all was the rebellious William Brown although this book has more of Billy Connolly than of Richmal Crompton. A compelling read.”

Professor Paul Preston, LSE