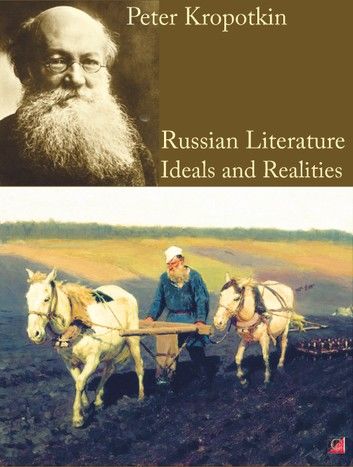

THIS book originated in a series of eight lectures on ‘Russian Literature during the Nineteenth Century’ which Peter Kropotkin delivered in March 1901, at the Lowell Institute, in Boston. Given the impossibility of exhausting so wide a subject as Russian Literature within the limits of one book, Kropotkin focused his attention on modern literature. The early writers, down to Púshkin and Gógol — the founders of the modern literature — he deals with in a short introductory sketch. The most representative writers in poetry, the novel, the drama, political literature, and art criticism, are considered next, and round them the author has grouped the less prominent writers, of whom the most important are mentioned in short notes. Kropotkin is fully aware that each of the latter presents something individual and well worth knowing; and that some of the less-known authors have even succeeded occasionally in better representing a given current of thought than their more famous colleagues; but ‘Russian Literature. Ideals and Realities’ is a book intended to provide only a broad, general idea of the subject.

Literary criticism has always been well represented in Russia, and the views taken in this book must needs bear traces of the work of the country’s great critics: Byelínskiy, Tchernyshévskiy, Dobrolúboff, and Písareff, and their modern followers, Mihailóvskiy, Arsénieff, Skabitchévskiy, Venguéroff, and others.

In the first chapter Kropotkin recounts the hard lot which befell the freemason Nóvikoff, the Christian mystic Lábzin, and the political writer Radischeff; but he also might have shown how a whole generation of ‘intellectuals’ was persecuted at the same time, with the intention of weeding out the ideas of the British eighteenth-century philosophers, the French encyclopaedists, and the French Revolution, and how the teachings of the German mystics and metaphysicians — Schelling, Fichte, and Hegel — penetrated instead. Since that time the persecutions never ceased, taking an especially acute character every twenty years or so, when whole generations of writers and thinkers saw their intellectual leaders arrested, exiled, or sent to hard labour, while the remaining ones lived under the menace of a similar fate. The generation of Púshkin, Odóevskiy, and Ryléeff — the so-called Decembrists of 1825, of whose sad fate Kropotkin writes in Chapter II of this book — was followed in 1849 by the ‘circles’ of Petrashévskiy, where the teachings of the French Socialists — Fourier, Cabet, and Pierre Leroux — were discussed. The result being that again a whole generation, including Dostoyévskiy, the critics Byelínskiy and Maykoff, the satirist Schédrin, the poet Pleschéyeff, and quite a number of men of mark who played later on a prominent part in the work of liberation of the serfs, was accused of a dangerous conspiracy, arrested, condemned to be shot, sent to hard labour, or exiled.

Then came, after a short interval of relative freedom, the persecutions of 1863, and with them began the era of uninterrupted persecutions of literature, art, science, and the Universities, which lasted till the year 1905. These were years when nearly every one of the younger writers had to make acquaintance with imprisonment or exile, and these were periods when in almost every intellectual family there was some one of its members or friends in prison or in exile. No wonder that all joy of life disappeared from the literature of those years. How could a novelist depict the happiness of existence in this beautiful world, when nowhere he could see that happiness? Tchéhoff’s sad irony and Górkiy’s angry rebellion were a necessary outcome of real life.

But even amidst the gloomy conditions of those years Russian literature remained true to its mission. It retained its inner force, its vitality, its capacity of discussing all the great problems of European civilisation, even under the strokes of the censor and the menaces of an omnipotent State’s police.