| FindBook |

有 1 項符合

The Meaning of Anarchism的圖書 |

|

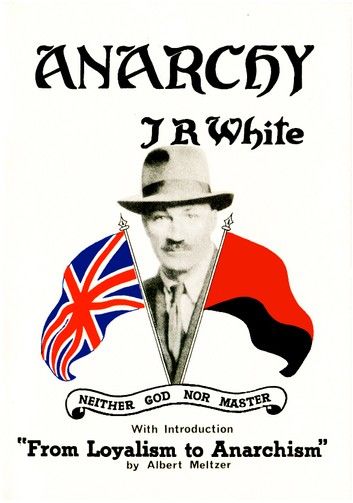

The Meaning of Anarchism 作者:Capt. Jack White,Albert Meltzer 出版社:ChristieBooks 出版日期:2014-10-17 語言:英文 |

| 圖書館借閱 |

| 國家圖書館 | 全國圖書書目資訊網 | 國立公共資訊圖書館 | 電子書服務平台 | MetaCat 跨館整合查詢 |

| 臺北市立圖書館 | 新北市立圖書館 | 基隆市公共圖書館 | 桃園市立圖書館 | 新竹縣公共圖書館 |

| 苗栗縣立圖書館 | 臺中市立圖書館 | 彰化縣公共圖書館 | 南投縣文化局 | 雲林縣公共圖書館 |

| 嘉義縣圖書館 | 臺南市立圖書館 | 高雄市立圖書館 | 屏東縣公共圖書館 | 宜蘭縣公共圖書館 |

| 花蓮縣文化局 | 臺東縣文化處 |

|

|

Captain Jack White (1879-1946). Any study of anarchism anywhere in Ireland would be amiss if it did not include mention of the first organiser of the Irish Citizen Army: republican, communist and then anarchist, Captain Jack White. Born at Whitehall, near Broughshane in County Antrim Jack White spent much of his childhood in England before joining the British Army and serving overseas. The details of Jack White’s early life are fairly well documented and highlight his relatively wealthy, landed Protestant upbringing, his uneasy transition to a British Army officer and his first major clash with Roman Catholicism. The Russian revolutionary uprising of 1905 appears to have had a singular effect on White and he was drawn particularly to Leo Tolstoy the eponymous creator of ‘Christian anarchism’ in the years after that event. Tolstoy’s pacifism probably appealed to White after his experiences in the Boer War. Soon afterwards he resigned his commission and left the Army, working for a while in Bohemia and then Canada (as a lumberjack), before moving to England and joining the anarchist commune at Whiteways, near Stroud in Gloucestershire where he remained until 1912 or early 1913. After a brief spell in Ulster he moved to Dublin where he was involved with a small group of intellectuals named the Civic League. The great working class upsurge of the 1913 Lockout was entering a crucial stage and White was an enthusiastic supporter of the Irish Trades and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU), and their strike against the capitalist oligarch and Irish nationalist newspaper baron, William Martin Murphy. White spoke and agitated alongside Jim Larkin and ‘Big Bill’ Haywood of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and initiated the idea and then commanded the concrete organisation of the Irish Citizen Army, a worker’s militia, originally the ITGWU at arms in a sense and, through James Connolly’s influence, pliable in the hands of the military council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in the lead-up to the Easter Rising of 1916.

Convinced as he was of the need for the unification of the labour and national movements, and clashing on this subject with Citizen Army secretary, Seán O’Casey, Jack White moved across to the Irish Volunteers and was dispatched to Derry to train the local corps. This liaison lasted but a short time when he encountered in Derry a strong sectarian antipathy and desire among local Volunteers to fight the rival Ulster Volunteer Force. At the outbreak of war White kitted out a field ambulance and joined an Australian medical force, but lasted only a short time before returning to England. By 1916 he was in south Wales and served three months in prison for trying to organise a strike by miners in opposition to the executions of the leaders of the Easter Rising. In subsequent years, and with a ban on him entering Ireland, White moved more towards a communist position and supported the attempts of the Socialist Party of Ireland to affiliate to the second world congress of the Communist International in Moscow in 1920. Asked to stand on a Worker’s Republican ticket in Letterkenny in County Donegal for the 1923 general election, White said he’d stand instead as a ‘Christian Communist’ and not as a republican, which he felt to be a ‘morally and politically unsound’ position. Unready as it was for such politics, Donegal rejected this response from White and he moved on to become actively involved with the abortive Irish Worker League, set up by Jim Larkin also in 1923 after the latter returned from the US. This venture was not a political party, embryonic or otherwise, and began to disintegrate in the wake of the Comintern’s slackening hope in Larkin. Indeed, the Revolutionary Worker’s Group (RWG) emerged in its place in 1930 and won the immediate support of Jack White and a great many ordinary workers. The RWG was yet another communist incarnation, but one that, by its involvement in the unemployed struggle particularly, achieved a heroic if short-lived status in the working class movement. In 1930, White produced his autobiography in which what comes across most strongly is his fierce independence of thought and action, his ironical self-effacement and his strong Ulster Protestant heritage. What remains behind is largely half a picture, insofar as the culmination of White’s political development towards anarcho-syndicalism is not included, coming as it did, in the later 1930s after his visit to revolutionary Spain. Fortunately, White’s pamphlet, The Meaning of Anarchism, published in 1937 has left us a strong sense of his anarchist ideas. He wrote, for example, ‘to destroy the state, one must not begin by becoming the state; for in doing so one becomes automatically its preserver’. Instead, he held, that to abolish the state and class society non- hierarchical, bottom-up self-organisation was the only way forward for the working class, and anarcho-syndicalism in Spain had shown that way. This was because, ‘anarcho-syndicalism applies energy at the point of production; its human solidarity is cemented by the association of people in common production undiluted by mere groupings of opinion’.

Jack White returned to Belfast in 1931, and as in Dublin nearly twenty years previously, signalled his support for the unemployed demonstrators of East Belfast with a vigorous physical assault (this time minus a hurley stick) on the police who were trying to break up the protestors. White was in East Belfast in solidarity with the unemployed and as a member of the RWG, and spent a month in prison for his defence of the street protest. More damaging was the exclusion order served on White as he emerged from Crumlin Road gaol, and which effectively put an end to his political activity north of the border.

In 1936 went to Spain with a British Red Cross unit and later linked up with the Irish ‘Connolly Column’ of the International Brigades where he clashed with Frank Ryan, a leading member of the Irish Communist Party. It was there he became thoroughly disenchanted with Stalinist communism and aligned himself firmly with the Spanish anarchists of the CNT-FAI, and on returning to London set up an arms smuggling enterprise to the anarchists via Czechoslovakia and Germany. Meltzer, who himself had a family connection with Ballymena, helped out in this enterprise by ‘invoice typing and listening to White endlessly relating the crimes of the Catholic Church’. The channel was closed down, however, when the Germans alerted London about this surreptitious breach of the Non-Intervention Pact, and the Captain confined himself to activism with the pre-war Freedom Group, arbitration among the divided anarchists of Glasgow, and the production of an Irish anarchist labour history survey with the Liverpool Irish anarchist, Mat Kavanagh. After a brief period in a Belfast nursing home White died in 1946 and was buried in the graveyard adjoining Broughshane First Presbyterian Church.

Jack White’s journey towards anarchism began many years before his embrace of nationalism or communism, and although his conversion to anarcho-syndicalism came later, his libertarian ideas were the defining political motif of his life. He had, since boyhood, already carried a total detestation of the villainous and shameless tyrannical hypocrisy and doublespeak of the Roman Catholic Church, as a set of ideas completely without rancour or bigotry towards individual Catholics. His subsequent experiences of the de-humanising authoritarianism and barbarity of the Army and war set him on a path that never thereafter veered too far from a solid libertarian socialism.

|