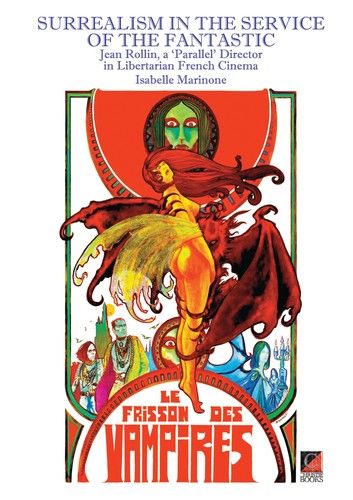

What dyed-in-the-wool cinephiles have always stupidly misinterpreted as amateurism, nonchalance or ineptitude on Rollin’s part (his disregard for linearity and logic, the influence of theatricality and pataphysics on his thoughts about directing, his well-meaning curiosity for erotic deviancy, his passion for the melodramatic) comes fully into its own as an aesthetic and, may we say, ideological option […] We are transported simultaneously into a Clovis Trouille painting or a Gaston Leroux novel, into a Max Ernst collage and a Grand Guignol play, into the gaudy cover of some old Fantômas and an episode from a silent serial, into The Castle of Otranto and the cavern of The Phantom in Bengal. Swimming against the tide of pyrotechnics in movies that confuse car chases and action, conventions and daring innovations, and digital trickery and mise en scène, Jean Rollin steers us back towards cinema. Genuine cinema, the sort that can make us shudder and cry, the sort that can leave us walking on air.

Jean-Pierre Bouyxou, “La Fiancée de Dracula”, foreword to Pascal Françaix’s Jean Rollin, cinéaste écrivain (Paris: Éditions Films ABC, 2002)