The woman scientist who saved Americans from thalidomide

In the early 1960s, Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration became one of the most celebrated women in America when she prevented a deadly sedative from entering the U.S. market. A Canadian-born pharmacologist and physician, Kelsey saved countless Americans from the devastating side effects of thalidomide, a drug routinely given to pregnant women to prevent morning sickness. As the FDA medical officer charged with reviewing Merrell Pharmaceutical’s application for approval in 1960-61, Kelsey was unconvinced that there was sufficient evidence of the drug’s efficacy and safety. Despite substantial pressure, she held her ground for nineteen months while the extent of the drug’s worldwide damage became known-thousands of stillborn babies, as well as at least 10,000 children across 46 countries born with severe deformities such as missing limbs, arms and legs that resembled flippers, and improperly developed eyes, ears, and other organs. As a result of Kelsey’s efforts, thalidomide was never sold in the United States. The incident led Congress to pass the 1962 Drug Amendment, which fundamentally changed drug regulation in America. Those regulations, still in force today, required pharmaceutical companies to conduct phased clinical trials, obtain informed consent from participants in drug testing, and warn the FDA of adverse effects, and it granted the FDA important controls over prescription-drug advertising. One of a small minority of women to earn an advanced degree in science in the 1930s, Kelsey faced challenges that resonate with women scientists to this day. Revered by the public as a "good mother of science," she went on to act as a formidable gatekeeper against other suspect drugs, such as diesthylstilbestrol (DES) and laetrile. As part of the team that tested anti-malarial drugs on prisoner volunteers during World War II, she later was instrumental in the formulation of ethical protocols for drug testing on prisoners and the vulnerable, including the elderly and children. Yet behind the public adulation, she faced professional jealousies and glass ceilings, political interference with FDA’s actions, and ongoing hostility from pharmaceutical industry officials. She was sustained and supported by family and friends, co-workers and mentors, and a lifetime commitment to good science. Based upon FDA archival records, private family papers, and interviews with family and colleagues, this biography brings to light the efforts and legacy of a pioneering woman of science whose contributions are still influential today.| FindBook |

有 1 項符合

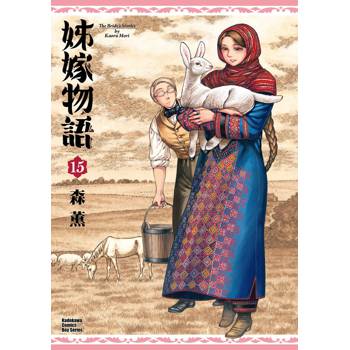

Frances Oldham Kelsey, the Fda, and the Battle Against Thalidomide的圖書 |

|

Frances Oldham Kelsey, the Fda, and the Battle Against Thalidomide 作者:Warsh 出版社:Oxford University Press, USA 出版日期:2024-05-21 語言:英文 規格:精裝 / 288頁 / 普通級/ 初版 |

| 圖書館借閱 |

| 國家圖書館 | 全國圖書書目資訊網 | 國立公共資訊圖書館 | 電子書服務平台 | MetaCat 跨館整合查詢 |

| 臺北市立圖書館 | 新北市立圖書館 | 基隆市公共圖書館 | 桃園市立圖書館 | 新竹縣公共圖書館 |

| 苗栗縣立圖書館 | 臺中市立圖書館 | 彰化縣公共圖書館 | 南投縣文化局 | 雲林縣公共圖書館 |

| 嘉義縣圖書館 | 臺南市立圖書館 | 高雄市立圖書館 | 屏東縣公共圖書館 | 宜蘭縣公共圖書館 |

| 花蓮縣文化局 | 臺東縣文化處 |

|

|

圖書介紹 - 資料來源:博客來 評分:

圖書名稱:Frances Oldham Kelsey, the Fda, and the Battle Against Thalidomide

內容簡介

作者簡介

Cheryl Krasnick Warsh is Professor of History at Vancouver Island University in Nanaimo, Canada. Dr. Warsh has published books on the history of asylums, women’s health, children’s health, consumerism, and alcohol and drug use. She served as long-term editor-in-chief of the Canadian Bulletin of Medical History and was co-editor of Gender & History. Dr. Warsh was a Fulbright Fellow, AMS/Hannah Fellow, and the inaugural recipient of the Vancouver Island University Distinguished Researcher Award. In 2017, she was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada for her contributions to Canadian medical history.

|