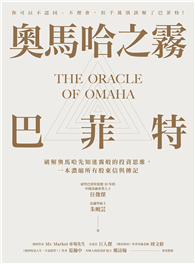

Recovered in 1755 during excavations in the Villa dei Papiri in Herculaneum, the prosciutto sundial is the earliest known portable Roman sundial. Palm-sized and in the shape of an Italian cured ham, its silver-plated cast bronze form cleverly combines an accurate modelling of a prosciutto with a relatively sophisticated scientific device capable of capturing the seasonal hours of the zodiacal year by employing the pig’s tail to cast the sun’s shadow onto the dial. This book explores the significance of this curious object’s discovery in the Villa dei Papiri and offers the first comprehensive survey of its reception and analysis by drawing on contemporary correspondence and manuscripts, travel journals, popular accounts, archaeological studies, and scientific and horological assessments.

Christopher Parslow shows how the prosciutto sundial is a rare example of an ancient artifact that has attracted the attention of a very broad audience, from archaeologists, art historians, and philologists to astronomers, philosophers, and sundial aficionados. The backdrop to its history features bitter infighting in the Bourbon court, clandestine descriptions circulating on the international scholarly network, and jockeying for preeminence among scholars in the learned foreign academies. Despite this long history, no scholar has treated the prosciutto adequately in full or analyzed it correctly because they lacked crucial evidence available only by examining the actual object in detail. Parslow addresses that shortcoming by providing results obtained through a 3D model to offer the first empirical analysis since the initial assessment by the Bourbon court of the prosciutto’s remarkably accurate capabilities as a timepiece.| FindBook |

有 1 項符合

The Prosciutto Sundial: Casting Light on an Ancient Roman Timepiece from the Villa Dei Papiri in Herculaneum的圖書 |

|

The Prosciutto Sundial: Casting Light on an Ancient Roman Timepiece from the Villa Dei Papiri in Herculaneum 作者:Parslow 出版社:Oxford University Press, USA 出版日期:2024-10-03 語言:英文 規格:精裝 / 368頁 / 普通級/ 初版 |

| 圖書館借閱 |

| 國家圖書館 | 全國圖書書目資訊網 | 國立公共資訊圖書館 | 電子書服務平台 | MetaCat 跨館整合查詢 |

| 臺北市立圖書館 | 新北市立圖書館 | 基隆市公共圖書館 | 桃園市立圖書館 | 新竹縣公共圖書館 |

| 苗栗縣立圖書館 | 臺中市立圖書館 | 彰化縣公共圖書館 | 南投縣文化局 | 雲林縣公共圖書館 |

| 嘉義縣圖書館 | 臺南市立圖書館 | 高雄市立圖書館 | 屏東縣公共圖書館 | 宜蘭縣公共圖書館 |

| 花蓮縣文化局 | 臺東縣文化處 |

|

|

圖書介紹 - 資料來源:博客來 評分:

圖書名稱:The Prosciutto Sundial: Casting Light on an Ancient Roman Timepiece from the Villa Dei Papiri in Herculaneum

|