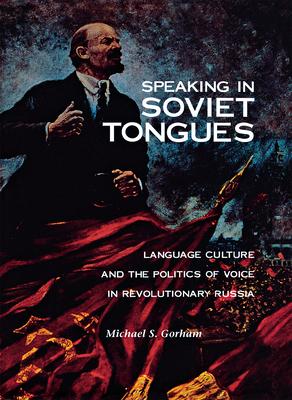

From the classical dialogues of Plato to current political correctness, manipulating language to advance a particular set of values and ideas has been a time-honored practice. During times of radical social and political change, the terms of debate themselves become sharply contested: how people reject, redefine, and reappropriate key words and phrases gives important symbolic shape to their vision of the future. Especially in cataclysmic times, who one is or wants to be is defined by how one writes and speaks.

The language culture of early Soviet Russia marked just such a tenuous state of symbolic affairs. Partly out of necessity, partly in the spirit of change, Bolshevik revolutionaries cast off old verbal models of identity and authority and replaced them with a cacophony of new words, phrases, and communicative contexts intended to define and help legitimatize the new Soviet order. Pitched to an audience composed largely of semiliterate peasants, however, the new Bolshevik message often fell on deaf ears. Embraced by numerous sympathetic and newly empowered citizens, the voice of Bolshevism also evoked a variety of less desirable reactions, ranging from confusion and willful subversion to total disregard. Indeed, the earliest years of Bolshevik rule produced a communication gap that held little promise for the makings of a proletarian dictatorship. This gap drew the attention of language authorities--most notably Maxim Gorky--and gave rise to a society-wide debate over the appropriate voice of the new Soviet state and its citizenry. Drawing from history, literature, and sociology, Gorham offers the first comprehensive, interdisciplinary analysis of this critical debate, demonstrating how language ideologies and practices were invented, contested, and redefined. Speaking in Soviet Tongues shows how early Soviet language culture gave rise to unparalleled verbal creativity and utopian imagination while sowing the seeds for perhaps the most notorious forms of Orwellian "newspeak" known to the modern era.| FindBook |

有 1 項符合

Speaking in Soviet Tongues: Language Culture and the Politics of Voice in Revolutionary Russia的圖書 |

|

Speaking in Soviet Tongues 作者:Gorham 出版社:Northern Illinois University Press 出版日期:2003-06-02 語言:英文 規格:精裝 / 277頁 / 23.6 x 16.3 x 2.8 cm / 普通級 |

| 圖書館借閱 |

| 國家圖書館 | 全國圖書書目資訊網 | 國立公共資訊圖書館 | 電子書服務平台 | MetaCat 跨館整合查詢 |

| 臺北市立圖書館 | 新北市立圖書館 | 基隆市公共圖書館 | 桃園市立圖書館 | 新竹縣公共圖書館 |

| 苗栗縣立圖書館 | 臺中市立圖書館 | 彰化縣公共圖書館 | 南投縣文化局 | 雲林縣公共圖書館 |

| 嘉義縣圖書館 | 臺南市立圖書館 | 高雄市立圖書館 | 屏東縣公共圖書館 | 宜蘭縣公共圖書館 |

| 花蓮縣文化局 | 臺東縣文化處 |

|

|

圖書介紹 - 資料來源:博客來 評分:

圖書名稱:Speaking in Soviet Tongues: Language Culture and the Politics of Voice in Revolutionary Russia

|