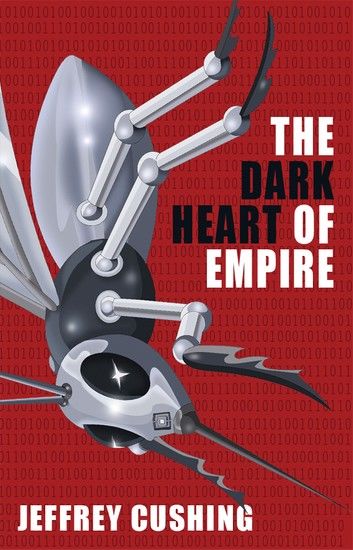

Drones already circle in the skies above us. The technology of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) seems to jump by leaps and bounds in an era of rapid growth and transformation not seen in aviation since the dawn of the jet age. An ever-increasing number of nations clamor to join the elite club of those with UAV technology. New companies spring up with innovative designs and missions; established companies announce new capabilities in endurance and networking. And people wonder whether arming UAVs is an acceptable tactic and weapon or simply the high-tech equivalent of murder.

What defines the battlefield? And if everywhere is a battlefield, then wouldn’t a soldier or airman in a trailer who controls the drone from thousands of miles or even continents away just as equally be on the battlefield?

These are all reasonable questions and ones that are finding their way into headlines with increasing frequency as the global network of drone bases ever more rapidly expands. These drones often have names that inspire fear as well: Predator, Reaper, Sentinel, Raven. There is a sense of intimidation and menace about them. Perhaps one reason is that UAVs fulfill the promise that death can be delivered almost anywhere, silent and undetected, until it’s too late.

Surely whoever controls such awesome power will have a revolutionary new ability in their hands. Won’t fear of constant surveillance and invisible death ensure absolute domestic conformity and hence absolute tyranny?

These are questions we must ask ourselves if democracy is to survive as a viable form of government. For what power has ever been more dangerous to democracy than giving its leaders the ability to kill without accountability or even detection? Fortunately, history provides us with a number of guideposts to light the way and shows us the inevitable consequences of the continuing development of this amazing new technology.

In the Republic, Plato tells the story of a shepherd who, while tending his flocks, experienced a great earthquake that revealed the entrance to a cave. The shepherd climbed down and saw many great and wondrous things. In the center of the cave lay a corpse with a golden ring still on its hand. The shepherd took the ring and put it on his own finger. By turning this ring he discovered that it had the power to make himself invisible.

The shepherd left the cave and eventually found his way to the royal court and castle. There, with the help of his ring, he succeeded in seducing the Queen, and with her help, murdered the king and took the throne, placing the crown of kingship on his own head.

Given such power, Plato asks, would anyone have the iron strength of will necessary to do good as the only true path to happiness, or as Plato calls it, the true health of the soul? Or would each of us inevitably succumb to the temptation to be the absolute master of all you survey?

How each of us answers this question will help determine whether we – as individuals or all together – are on the road to a new era of justice and peace, or merely on the well-worn path to the graveyard of empires.

![[隨書附贈「日進斗金X財源滾滾」吊飾]詹惟中2025開運農民曆:風水名師詹惟中的獨創開運書,金蛇年流年神準分析,八大運勢詳細解說,保證讓你2025年,財運、功名、桃花、人脈運勢看漲! [隨書附贈「日進斗金X財源滾滾」吊飾]詹惟中2025開運農民曆:風水名師詹惟中的獨創開運書,金蛇年流年神準分析,八大運勢詳細解說,保證讓你2025年,財運、功名、桃花、人脈運勢看漲!](https://media.taaze.tw/showLargeImage.html?sc=11101046125)