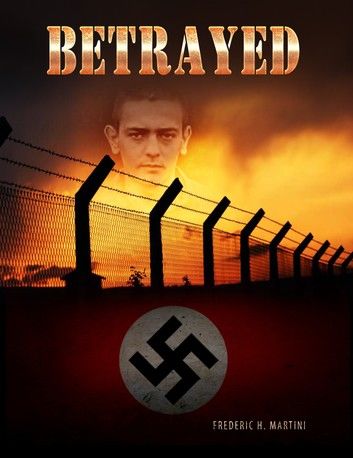

In June 1944, Staff Sergeant Frederic C. Martini, was a waist gunner on a B-17 with the 385th Bomb Group. On his ninth combat mission, his aircraft was downed by antiaircraft fire. Fred was sheltered by the French Resistance for two months, until he was lured away by a double agent, with promises of an escape route to Allied lines. Betrayed to the Gestapo, he was interrogated, sentenced to death as a spy, and loaded into a boxcar with other Allied airmen captured under similar circumstances. After a five day ordeal, 168 of them arrived at Buchenwald Concentration Camp to await execution.

While at Buchenwald, the airmen were beaten, starved, interrogated, and given experimental injections, and Fred survived a burst appendix. After nine weeks, two of the airmen were dead and the rest barely hanging on. The airmen who survived Buchenwald did so only because the Luftwaffe ignored Himmler’s orders and shifted them to Stalag Luft III. However in January 1945, the Buchenwald airmen were marched in a blizzard across Poland ahead of the advancing Russians. Men fit for transport at the end of this march were carried by boxcar to Stalag VIIA, near Munich. Sergeants like Fred were used as forced laborers, clearing bomb damage under fire until the 120,000 POWs held at Stalag VIIA were liberated by Patton’s 3rd Army on 29 April 1945.

Buchenwald was the primary labor supply for the Mittelwerk V-2 factory at Nordhausen/Dora, where the famous rocket scientist Wernher von Braun personally selected skilled prisoners as slave laborers for his projects. At the end of the war, the Joint Chiefs were convinced that German scientists and engineers – especially those associated with the rocket program – would be invaluable assets in the war against Japan or a future conflict with the Soviet Union. Soon after von Braun and his associates surrendered to the US military, all records of the Mittelwerk and of the Buchenwald airmen were classified and became unavailable to war crimes prosecutors, Congressional Committees, and the Veterans Administration. The official position of the British and American governments was that no Allied POWs had been held in German concentration camps.

Under Project Paperclip, von Braun and over 1700 other Nazi technocrats were relocated to the US. For the next 40 years the US intelligence agencies (the OSS/CIA, Army G-2, and an intelligence subcommittee of the Joint Chiefs) concealed or misrepresented von Braun’s wartime history and his involvement with slave labor, assuring the Department of State, the Department of Justice, the President, and the American public that von Braun was apolitical and uninvolved in Nazi war crimes. Awkward questions by the press and publications that could expose von Braun’s activities and his SS rank were repeatedly suppressed.

Over the same period the Army refused to acknowledge what the Buchenwald airmen had experienced, and their military records remained sealed and unavailable to other governmental agencies. As a result, the men were denied VA pensions and coverage for medical problems related to their time in Buchenwald. The airmen were treated as liars or as delusional psych cases. Fred, for example, received a 10% psychological disability, granted for chronic anxiety, “imaginary” foot problems, and for claiming to have been in Buchenwald. The VA refused to revise their determinations even after the release of documentation validating the airmen’s claims and despite the recognition of medical conditions, such as PTSD and peripheral neuropathy, that were not understood in 1945.

This book focuses on Fred Martini’s experiences, but integrates the experiences of the other Buchenwald airmen through their own statements and wartime records declassified since the 1980s. It interweaves the story of Wernher von Braun, documenting the full extent of the postwar cover-up and the impact the security program had on the lives of the Buchenwald airmen.