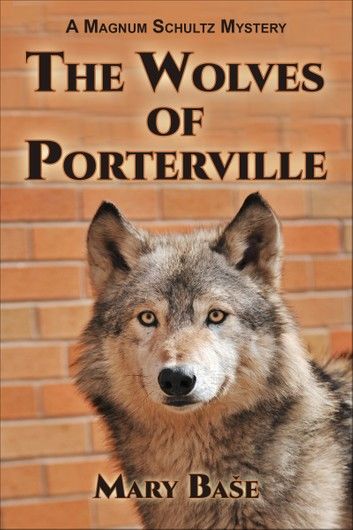

Amorak. That word pops into my brain and I don’t even know what it means until I consult a present-day shaman who takes me on a shamanic journey. Among other things, I learn that amorak is a First Nations word which means wolf. And that my animal spirit guide is telling me to watch out for an evil predator.

Yeah, right. I’m a police detective and a mother of a 15 year old; what are the chances I’m going to put any faith in that kind of crap? Yet when I run a stolen car full of bank robbers off the road, and one of the felons is an Inuit man from the Yukon, strange things begin happening—bizarre dreams, visions of malevolent eyes, instances of psychokinesis.

Retired anthropology professor, Richard Morris, has harbored a lifelong interest in First Nations people and begs for an opportunity to meet the Inuit bank robber. When he comes to Porterville’s jail he brings books about First Nation cultures and a box of Inuit artifacts he thinks the man will find interesting. Of course I look through the box to check for contraband before allowing it into the prisoner. Oops! An ancient flint-bladed knife is removed from the box and remains behind on my desk.

The felon, Julius, inspects the artifacts with fascination but observes, “At my parents’ home in Whitehorse, I have a knife—much like the one left behind on Miss’s desk.”

“Did...how...?” I splutter.

“I see it, Miss,” says Julius. “I also see a black spirit which my mother sends from Whitehorse to help you fight the evil predator.”

After the visit between Julius and Professor Morris, someone has removed the knife from my desk. It is nowhere to be found until it shows up days later in a cold, dark cellar and comes in handy for cutting the duct tape bonds which imprison a beautiful pole dancer and me.

With all this, I begin to question whether or not our world isn’t more than just facts and evidence.

A serial rapist is on the loose and strikes in Lincoln County, in Porterville, even on the ESU campus, leading me to work closely with Campus Police Officer Jaydeen Huff putting both of us in peril so that, finally, I find myself desperately calling her name in the dark subterranean tunnels beneath the university. Then I find her:

Quentin’s murderous glare sears into me.

“Why?” he asks softly, through gritted teeth. He raises Jaydeen by the hair and pulls her to her feet, an effective shield, against his chest. “Why can’t you bitches just learn your place?” The voice increases in volume and pitch. “I’ve tried to teach you all your place!” Now he is crescendo-ing. “But you just don’t get it! We all have our places in this world; yours is not above man! Now this one will have to die and so will you.”

To complicate matters, my philandering husband wants a divorce. Since I’m feeling a little vulnerable, I get the hots for a good looking, double-dimpled deputy from Stevens County.

George Rooney, a bounty hunter of whom I’ve never been fond, flips his Ford Bronco upside down in a torrential down-pour, causing my daughter to be late for her birthday party so that we can save his sorry ass. Then we learn that the bail jumper Rooney was transporting from the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana has escaped. This guy enjoys setting people he doesn’t like on fire. And now he’s loose in my jurisdiction. Then as if things weren’t touchy enough, Rooney has the gall to suggest that I might just be his daughter.