| FindBook |

有 1 項符合

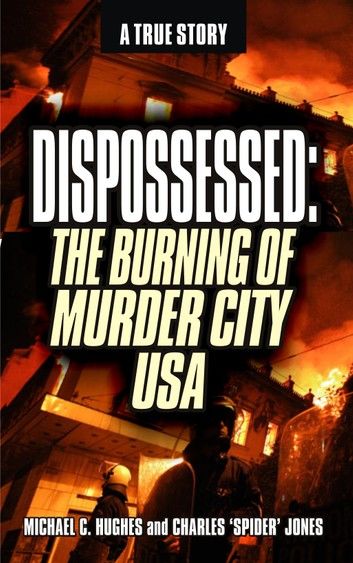

DISPOSSESSED的圖書 |

|

DISPOSSESSED 作者:Michael C. Hughes,Charles 'Spider' Jones 出版社:Michael Hughes 出版日期:2017-04-14 語言:英文 |

| 圖書館借閱 |

| 國家圖書館 | 全國圖書書目資訊網 | 國立公共資訊圖書館 | 電子書服務平台 | MetaCat 跨館整合查詢 |

| 臺北市立圖書館 | 新北市立圖書館 | 基隆市公共圖書館 | 桃園市立圖書館 | 新竹縣公共圖書館 |

| 苗栗縣立圖書館 | 臺中市立圖書館 | 彰化縣公共圖書館 | 南投縣文化局 | 雲林縣公共圖書館 |

| 嘉義縣圖書館 | 臺南市立圖書館 | 高雄市立圖書館 | 屏東縣公共圖書館 | 宜蘭縣公共圖書館 |

| 花蓮縣文化局 | 臺東縣文化處 |

|

|

In 1920, Detroit was a bustling city of almost a million people. It was also the most technologically advanced and fastest growing city on the entire planet at the time. All thanks to the auto assembly line that was invented there and had been booming since Henry Ford rolled out the first Model T in 1908.

A city with the brightest of futures.

By 1950, Detroit was known as Motor City, and was one the main engines driving American prosperity. The population had swelled to two million and Detroit still had the brightest future in America. But problems were already setting in. Unemployed blacks fleeing poverty of the Deep South were arriving in numbers so large even the automakers couldn’t provide jobs for everyone. Migration into the city was proving to be a slow-burning fuse. GIs ―both black and white―who had returned from WWII did not want to fight again for jobs on the lines. Nor did other blacks already living in the city lucky enough to have jobs with the Big Three: Ford, GM, and Chrysler. Many new arrivals faced limited job prospects and simply gave up and went on the welfare rolls to survive.

By the 1960s, Detroit had become even better known as Motown, one of the new music capitals of the world. But it was also slipping into a place of Darwinian struggle—survival of the fittest and the most desperate: too many still fighting for jobs available.

By the mid ‘60s bitterness and racial tensions had set in. Not just tensions between blacks and the almost all-white police force, but just as much between blacks and blacks. Downtown Detroit began to empty of white people entirely as they fled by the thousands to the suburbs and small towns outside the city, which left blacks to war with each other for very limited downtown turf. The city core was spinning out of control and Detroit was eventually overtaken by a mindless kind of violence. Attacks for no reason: violence for the sake of striking out at someone. Anyone. No one was safe downtown any more.

By 1967 the city had earned an entirely new name: the sickening epithet Murder City USA. The highest murder rate in America for many years in a row by then. The people who lived there, feeling trapped and with no way out, could see and feel the city unraveling. They knew they were living in a powder keg.

Then, in the small hours of a searing Saturday night in July of that year, it blew.

For four days Detroit was filled with gunfire and looting as the city burned. More a Vietnam battle zone than a once-great American city.

When it was over, forty-three were dead, many hundreds were injured, and more than fourteen hundred homes, buildings, and businesses were burned and leveled. Much of the area around 12th Street was a burned-out smoldering ruins. An area many blacks called Blackbottom, the heart and soul of old black Detroit, died in those four days.

Many saw the trouble coming. Lived with it with growing anxiety as they grew up and saw where the city was headed. Saw the fuse burning. A great city with a once shining future turned into a massive disheartening soul-crushing ghetto where so many were trapped when what had become an urban hellscape began to burn.

One of those live there and saw it all coming in person was my good friend Spider Jones. He saw, as a boy growing up, all the signs of a city primed to blow. And he was there that fateful night when the first bottle smashed against the wall at 2:00 a.m. and he got sprayed by glass shards as rioting took hold all around him. They swept through downtown with a life of their own, moving as fast as the flames.

Spider got out alive—barely. But he grew up there to see it all unfolding.

In the Sixties, as Detroit was going from being known as Motor City, to Motown, to Murder City, ninety per cent of murders were black-on-black. A city turning in on itself.

Something insidious had set in. Driving this state of desperation was the fact that downtown Detroit black people had become the Great Dispossessed. People with nothing. In the Blackbottom and 12th Street area of black downtown Detroit, there were almost no black owners of houses, apartments, stores, or businesses. Downtown Detroit was virtually one hundred per cent owned by absentee landlords, virtually all white, and most from many from miles away, even from other states and cities: Chicago, Philadelphia, New York. Owners didn’t see or care about the day-to-day carnage: they just wanted their rents.

According to Spider, black people came to hate themselves for having got into the position of having nothing and having little chance of ever getting anything. They hated that they had be driven into rat-infested corners to live with the rats. They hated that they allowed themselves to be driven to live that way. And two things happened: rage and desperation rose as self-esteem plummeted and self-loathing took hold. Then, when the match was lit, the great dispossessed of Detroit turned on themselves.

Spider saw it all happen. He also felt the undermining grind of low self-esteem and through it all he, personally, never lost sight of his own dreams. But he will tell you today that low self-esteem and depression undercut everybody and everything around him as he grew up and continued to plague him for much of his life. He finally beat what he calls “those two demons,” depression and low self-esteem, and managed to achieve his dreams, to be a singer, a successful radio personality, and a busy motivational speaker doing his best to help young people.

But he went through a hell he calls Dee-troit to get there.

This is Spider’s story. A chronicle of the years leading up to the riots of ’67 and those four nights and days in the firestorm.

- Michael Hughes

|