| FindBook |

有 1 項符合

The Shiva的圖書 |

|

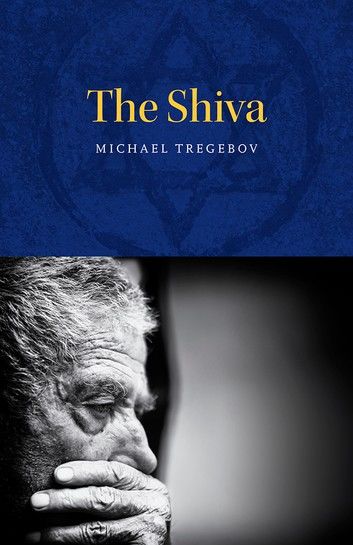

The Shiva 作者:Michael Tregebov 出版社:New Star Books 出版日期:2014-12-30 語言:英文 |

| 圖書館借閱 |

| 國家圖書館 | 全國圖書書目資訊網 | 國立公共資訊圖書館 | 電子書服務平台 | MetaCat 跨館整合查詢 |

| 臺北市立圖書館 | 新北市立圖書館 | 基隆市公共圖書館 | 桃園市立圖書館 | 新竹縣公共圖書館 |

| 苗栗縣立圖書館 | 臺中市立圖書館 | 彰化縣公共圖書館 | 南投縣文化局 | 雲林縣公共圖書館 |

| 嘉義縣圖書館 | 臺南市立圖書館 | 高雄市立圖書館 | 屏東縣公共圖書館 | 宜蘭縣公共圖書館 |

| 花蓮縣文化局 | 臺東縣文化處 |

|

|

Like Michael Tregebov's debut novel The Briss, which was a finalist for the Commonwealth First Novel Award (Canada–Caribbean Region), The Shiva is a fast–paced character–driven novel.

Failures in business and marriage tip poor Mooney into a spell in a psychiatric ward. But he has the great fortune of befriending an Indian seer, one of his pals from the casino where Mooney hangs out, who promises to put Mooney's life back together.

Dennis is no ordinary Indian seer. For one thing, he's a rez Indian, from right around Winnipeg, just like Mooney. For another, he's a stock picker, and what he sees coming, in the spring of 2008, is the sub–prime mortgage meltdown. So he puts together a consortium of himself, Mooney, and a bunch of Mooney's pals from the world of North End Winnipeg, to pool their savings in a short–selling scheme to cash in on the coming crash.

But the so–called "Eisenteeth syndicate" isn't just betting against the market. Mooney and his pals are betting against Mooney's brother Dave: crude, ignorant, maddeningly successful, whose oafish touch turns every business venture into gold. Did we mention their mother has something to say about all this?

Excerpt: Chapter 1

1

– Crap.

– Eisenteeth?

– Crap.

– I told you.

– Why didn’t you remind me at home?

– I did.

Who’s Eisenteeth? thought Mooney, standing in a rut of slush. It was Sammy and his wife Anna. Why are they waiting for Eisenteeth?

– We’re late, said Sammy.

– We can’t go in without Eisenteeth, said Anna.

– I’ll just cover my mouth.

– You’re not going in there like that.

– Stop mintering me.

– I’m not mintering you. I’m just saying.

Mooney tried to remember if he knew an Eisenteeth. He knew an Eisenberg, and an Eisenholt, and an Eisenberg, but no Eisenteeth.

– We’re late, said Sammy.

– So we’ll be a bit later. We’ve probably missed the ceremony.

– People will see us here.

– Everyone’s inside.

– Eisenteeth’s coming, said Anna.

Mooney looked around but saw no one coming. But he did see this:

Anna extracted Sammy’s uppers from her purse wrapped loosely in a hanky.

– Here, hold these.

Then she drew out his Xalatan eye drops and handed them to him. Sammy stood there, his uppers in his left hand and his eye drops in his right.

– How should we start?

– With the teeth, he said.

– Aw, Christ.

Sammy inserted his uppers halfway and then his wife pushed them in with her knuckles, an operation he was incapable of completing on his own. He ran his tongue over his teeth. Then Anna took the eye drops and administered one drop to each eye. Sammy blinked rapidly.

– Stand still, said Anna.

– It hurts.

– It doesn’t hurt. Are you alright.

– I’m tearing, said Sammy.

– Wipe your eyes.

– I’ll be okay.

– Wipe your eyes.

– Stop mintering me. It’s late.

– I’m not. I’ve finished mintering you.

– What’s this?

– This is the postmintering.

– OK. Let’s just go in already. Eisenteeth made it, said Sammy.

– You’d better pray that I live one day longer than you, that’s all I know.

– Oh, Mooney, I didn’t notice you, said Sammy.

– Hi, Sammy.

– What’s it going to be, Mooney?

– Same-old, same-old. And you?

– Ach, he said, wagging his hand, as if telling someone to leave.

– Hi, Anna.

– Mazel tov, Mooney. Your brother Dave must be very proud.

– Who’s Eisenteeth? Mooney asked them.

– Eyes and teeth. Sammy said, pointing to his running eyes and then his uppers. Eyes and teeth.

He recognized the Xalatan dispenser that Sammy was just now pocketing.

– Give me that, you’ll lose it, said Anna.

– It’s late.

Sammy opened one of the massive doors to the synagogue.

– Coming in, Mooney?

– I’m coming.

– How come you’re not inside already?

– Can’t stand the blood.

– What’s in the bag?

– Bagels for the bride.

– You’re bringing bagels to a briss?

And then they were swallowed up.

In a worn, sere overcoat, Mooney had trundled across the slushy pavements of a late winter’s morning snowfall and arrived at the synagogue complex, snowflakes twinkling on his whisk-broom eyelashes, carrying a brown paper bag with bagels from Sun’s bakery. Besides being squeamish, the reason he had arrived late was that he had to make a stop at the drugstore to refill his prescription of Xalatan, which his doctor had prescribed a few months ago for his glaucoma. ‘Kiss those thin eyelashes goodbye,’ the pharmacist had said on his first purchase of the drug. ‘With this you’re going to be accused of curling them.’ Then he added:

– You’re a bit young for glaucoma.

– There’s more glaucoma among young people than is commonly thought. Especially in African Americans.

– Not your case.

– In mine it’s hereditary. My father had it.

The pharmacist had handed Mooney the package in a plastic bag. Mooney opened his wallet, fingered the few grimy tens and tried to pay the man.

– You pay going out.

On the sidewalk again, he was cast adrift. Wasting time. The synagogue beckoned.

Once inside, his untied shoelaces were soaking wet. Look at my shoes, he said to himself. I can’t tie my laces properly. But his shoes were still on because they had been bought for him, a size too small. He held the sodden laces and miraculously he remembered how to tie a knot.

He stood before the carpeted vestibule, which was big enough to ride a bike across. Drawn to the empty main chapel first, he touched the benches appointed in blue velvet. He found it senza comfort. Was that the word for it? Comfortless? How did he know the Italian expression for what he wanted to say? Did he know Italian? Of course, he did. The electroshocks had frazzled his memory, but he hadn’t lost it. It was just as if someone had ransacked the filing cabinets in his head and jumbled up all the folders.

He had expected the chapel to comfort him. But there was no comfort there. The very size and brassiness of the two humongous menorahs pressed on his sternum.

And now he was now sitting around a table set with pink carnations in one of the overheated basement salons. He unknotted his tie in the torrid heat, taking in the humming of cheerful voices, trying to focus on a group of several young people, Richie Michaels’ girls, and then the cousins, to various degrees of consanguinity, of the mother and father of the tragic main character of the ceremony, who was now sequestered with his mother and father and grandmother, recovering from the first of the many shocks that would be coming his way.

Life, right from the start, was for the shits, Mooney thought. He was glad he had missed the ceremony.

They had sat him at the kids’ table, which was lavishly laid with hard-boiled eggs, cheese blintzes, herring, smoked salmon, hot fish, whipped cream cheese, potato pancakes, knishes, defrosted strawberries, bagels, and iced vodka and assorted beverages. His stomach was beginning to grumble pleasantly.

From time to time their server came by, scowled, and dumped fresh chunks of hot fish. After a week of bad food at home, the sight of the spread, the tablecloths and candles made him shiver with pleasure. But how did he get there? He had just been in the chapel.

The ‘cousins’ were boys and girls in their late teens and early twenties. They had their cell phones on the table and they giggled, when they weren’t laughing. And they needed nothing in particular to make them laugh. All it took was a message from someone: they’d say the name of the caller and they would all break up.

All the girls wore bangs, some to the right, some to the left, and, it seemed, two bras judging from the number of straps on their shoulders. And when one giggled, they all giggled. Why did they sit him at the kids’ table? But it was going to be a fun table, he thought, despite the ferocious temperature of the room. It’s the old people, he thought, they liked the heat up.

One of the boy cousins sitting next to him, hairy as a boar, Mooney thought, was wearing a T-shirt sporting the slogan ‘Got Home?’.

– What does that mean? Mooney asked, shooting his cuffs from the sleeves of his shiny brown suit. Hey you, I’m talking to you.

The young man chuckled.

– Me?

– Yes, you. What does ‘Got Home?’ mean. Mooney blinked at him.

– It invites you to make aliyah.

– To Israel?

– Where else?

Parched, Mooney took a drink of the iced vodka that was on the table. It was so cold it scalded his throat and he felt his thick eyelashes fill with water. It was something he had not had for a long time, but he recognized it as something he knew well. But it was different, like a miracle that you could swallow. He wiped his eyes with his immaculate napkin and then drained the shot glass.

– What’s your name?

– Jerry.

– I hear there are a lot of poor people in Israel, Jerry. Why would anyone want to go there?

– Myth. That’s a myth. They’re worse off here than in Israel.

– Who?

– The poor.

– I’m not sure I follow you, Jerry.

– Look, one out of every five Jews lives on the poverty line in America. One in seven below it. For example, in the US, in Chicago, there are two hundred and seventy-five thousand Jews, and one in five is poor. In NYC, one-quarter of the Jewish population live on or under the poverty line, with families of four earning less than twenty thousand a year. That’s three hundred and forty-eight thousand Jews living below the US Federal Poverty Line, in New York alone.

– That’s less than five thousand a year per head? said Mooney.

– Do the math.

– I did.

– The New York food bank last year gave away four and a half million pounds of kosher food to community food programs.

– What kind of kosher food? That’d include the blintz?

The boar-boy looked at Mooney suspiciously. It was hard to tell if Mooney was pulling his leg or not. But Mooney’s expression was pure, almost beatific. And with the others at the table listening, Jerry didn’t want to look like a fool, but he didn’t want to come off mean either.

– I think there’d be some blintzes.

– A little kreplach action, too, Jerry?

– I’d say that, too. I’d say there’d be some kreplach. Maybe a knish or two.

– But I can see there are no knishes at this table.

The girls at the table giggled, all except one, Rachel, a pretty girl, with large, square front teeth all seemingly filed to the same length, her lips just about covering them. The girl next to her explained the other meaning of knish.

– It’s like nebbish, but for a girl.

– What’s a nebbish?

– Someone who’s dull and boring.

– By the way, asked Mooney, why do they use nebbish for a man and knish for a woman? Anyone?

He drew a blank.

– Because you can go down on a nebbish but you have to eat a knish.

All the kids screamed, except Rachel.

– Getting back to our discussion, Mooney said to his companion, the other kids now listening attentively, let’s say you knew a Jew on welfare pulling in less than a thousand a month.

– Living alone?

– Like a prophet.

– He would be one of the poorest Jews in America, said Jerry.

– Well, that’s me, said Mooney.

– What do you mean?

– That’s me. I’m the poorest Jew in America. Should I move to Israel?

– You’re not really what they’re looking for there.

– Too old? Or too poor?

– You’d be a burden on the Jewish state.

– But there would be other poor people there, right?

– There are some poor people there. But the highest rate of Jewish poverty in the world, believe it or not, is in Brooklyn, maybe Montreal coming second.

– What about here?

– Probably the same as everywhere else. One out of five.

– Could you pass me the boiled bagels? Mooney asked him.

– All bagels are boiled. That’s why they’re bagels.

– So a bagel’s a bagel?

– That’s right. They’re all bagels.

– A bagel’s a bagel, you’re saying, right?

Jerry paused for a moment thinking about how to get out of the conversation. He finally just turned away from Mooney to talk to a cousin on his left.

After this affront, Mooney buttered his bagel and munched, followed by some pickled herring, which he chewed slowly, and then imbibed the vodka. He nudged his neighbour again. The other kids stopped talking.

– So a bagel’s a bagel?

– Yes!

– Jerry, you know there are basically two kinds of bagels. You do know that?

– I don’t really care.

– There’s the Montreal bagel, which is the sweetest and chewiest bagel because it’s boiled in honey-water and baked in a wood oven. It’s made with malt and egg but no salt.

– I know what’s in a bagel.

– So can you tell me what’s in a New York bagel?

– The same thing.

– No. In the New York bagel there’s no egg, and it’s boiled in tap water and baked in an ordinary oven. Voilà, it’s crustier and puffier than the Montreal bagel.

– But they’re both boiled! insisted Jerry.

Rachel asked:

– What kind of bagels are these?

– These are Montreal bagels, said Mooney.

– And these?

– The ones in that basket are New York bagels. What’s your name, sweetheart?

– Rachel.

– That’s a lovely name, Rachel. How old are you, dear?

– Nineteen.

– Is that not a beautiful thing? Do you know what Rachel means in Hebrew?

– No.

– Do you, Jerry? Do you?

– No.

– It means ‘ewe’.

– Oh.

– Now, Rachel, sweetheart, take one bagel from each basket and compare the crusts, Rachel. Just compare them.

Rachel picked up a bagel from each basket and tasted each one.

– He’s right. This one’s crustier. Rachel giggled, then went demure. That’d be the New York bagel?

– Are you studying, Rachel?

– I’m in pre-law.

– Pre-law. Isn’t that fantastic. Everyone should study the law. It’s the basis of civilization.

– But they’re both boiled! interrupted Jerry. There’s no such thing as fried bagels!

– Yes, said Mooney, there are no fried bagels, but there are bialys.

– What are bialys?

– Bialys are not boiled. The word comes from a city in Poland, Bialystok. Like the bagel, the bialys is also made with a chewy yeast dough. And it almost has the shape of a bagel, but the hole isn’t necessarily punched all the way through — that way you can fill it with onions or muhn — poppy-seed.

– I know what muhn is.

– But if the hole were punched through, would it not be an unboiled bagel, Jerry?

– I’ve never had a bialys.

– The bialys came to America at the same time as the bagel. Why do you think the bagel did so well, Jerry?

– Beats me.

– Would I be able to eat bialys in Israel?

The boar-boy didn’t know what to say, or why he was even having this conversation, and Mooney didn’t want to embarrass him with silence in front of the others at the table, who had been observing them. So he said:

– Could you pass me the herring, Jerry?

– Sure.

– You’re a good kid. How old are you, Jerry?

– Twenty.

Mooney speared himself a morsel of herring rolled around a pickled baby onion and waved it a bit in the air with his fork. Jerry watched Mooney and thought that he had finally been liberated, and turned away to talk to his cousin again.

– So, would I be able to eat bialys in Israel, Jerry?

– Well, you could certainly eat bagels.

– So you recommend the Israeli bagel.

– The Israeli bagel, like the Israeli orange, is the best in the world bar none.

The boy on Mooney’s right snickered. Jerry sneered at him.

– Should we, as a nation, be proud of our bagels?

– We invented the bagel, for fuck’s sake, said Jerry.

– What about the Russian booblik? Did we invent that?

– I’ve never heard of the booblik.

– You had never heard of the bialys either, which is really an unboiled bagel, although you said all bagels are boiled?

– I stand corrected. And no, I’ve never heard of the booblik.

– Which came first: the bagel or the booblik, Jerry?

– I just told you I don’t know what a booblik is.

The boy on Mooney’s right was relishing this. Mooney cocked his head to smile at him but then turned it back on Jerry.

– Isn’t it warm in here?

– No.

– Do you know where the booblik came from?

– I don’t know that either. How could I? I don’t know what a booblik is.

– The booblik came from Krakow, Poland, or maybe even Germany.

The pretty Rachel, with the astonishing teeth, asked:

– What is a booblik?

– You’re such a sweetheart, Rachel. You seem like the type of girl who has lived all her life with a baba at home, not in a home. The booblik is like a bagel, but it’s bigger and more compact, too dense in fact for a sandwich. It must be dunked.

– In what? asked the girl.

– Tea or coffee, sweetheart.

– So, it’s more of a pastry than a bagel? said the girl, intelligently.

– But in the bagel family, wouldn’t you say, Jerry?

– I don’t even want to be having this conversation. What’s your point, anyway?

– The point is, Jerry, I think you might have to retract your statement that the Jews invented the bagel.

– We did!

– And the bialys and the booblik? Look, bagel, bialys, booblik, whatever, Jerry, the truth is Eastern Europe has always had a strange relationship with its dough. Twisting and boiling it, or not. I don’t think the Jews invented the bagel — and you might be shocked to learn who did. And boiled dough might just go back to the Byzantines.

– A bagel’s a bagel! said the boar-boy, exasperated, making angled karate chops at his bagel with both hands. And bagel is a Jewish word.

– I’m not sure I’d agree with your etymology, Jerry.

Again the boy on Mooney’s right snickered. Mooney detected this boy had an animus where Jerry was concerned.

– What are you saying? that the bagel isn’t Jewish? There’s nothing more Jewish than a bagel.

Mooney picked up one of the Montreal bagels and held it in front of his eye as if it were a telescope and said:

– The first booblik-bagel or bagel-booblik, they say, was boiled and baked in Vienna, in the shape of a stirrup. It was 1683.

– You know the date of the invention of the bagel?

– No, of the word bagel. And I even know the time.

– You know the exact time the bagel was invented?

– Picture this: The Turks led by Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa, Visir of the Ottoman Empire during the reign of Mehmed IV, had just been defeated at the Battle of Vienna, as you know, by an outflanking cavalry charge led by a Jan Sobieski, King of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Down the hill he led his hussars at five in the afternoon on September 12, 1683, dashing the Turkish lines and putting the enemy to flight. At 5:30 PM, Sobieski, the ‘Saviour of Vienna’, as the Pope called him, the ‘Lion of Lechistan’, as the Turks called him, pulled his boots out of their stirrups and strode into the jaima of Kara Mustafa to discuss terms. And what’s the German word for stirrup, Jerry?

– I don’t know.

– Steigbügel, hence beigl in Yiddish and then eventually transliterated into ‘bagel’ in English. September 12, 1683 at 5:30 PM.

The kids at the table smiled, except Jerry, who looked at Mooney’s angelic face, and began with the karate chops.

– It’s just a bagel! Jerry said, and added even more karate chops to his bagel.

– But now, when you think of a bagel, the most Jewish thing you know, you must now think of a Pole, a Mr. Jan III Sobieski and his stirrups.

– It’s just a bagel!

– Just a bagel? And stop with the karate.

He held Jerry’s hand to stop him from chopping at the bagel.

– When a Jewish woman gave birth in Poland in the eighteenth century, what were you supposed to give her? Anyone? Rachel?

– A bagel? said Rachel.

– That’s right, sweetheart, said Mooney. And why a bagel, Jerry? Anyone? Rachel?

– Because her legs were in stirrups during birth? said Rachel.

– Thanks, but I’ll do the colour, Rachel, said Mooney.

– Don’t be so ridiculous, Rachel, said Jerry.

– You would give her a bagel, said Mooney, to celebrate the edict of Jan Sobieski that revoked the ban on Jewish baking in Poland. That’s why I brought my brother’s daughter-in-law these.

Mooney held up a brown paper bag of bagels from Sun’s bakery.

– You brought bagels to a briss? asked Jerry.

– You see, the bagel is practically a universal talismanic substance. A multicultural object par excellence.

Then he set the bag down on his lap and speared another piece of herring and, by placing it on his thickly buttered boiled bagel, turned the surface of the bagel a marbley blue and took a bite. He then poured himself another shot of vodka, which was still cold, and because he was still parched. Everyone went back to their eating and private conversations. He heard someone ask Rachel ‘what she was doing for fun this afternoon’.

Mooney, chewing slowly, wondered how he knew all this about the bagel. And Jan Sobieski and his cavalry charge against the Turks. It just came out, so his memory was intact, but just farmisht. He nudged his neighbour, interrupting his conversation with Rachel.

– Don’t you find it warm in here?

– No.

– Don’t turn away. I’m talking to you.

– What?

– I wanted to ask you how many poor people are there in Israel? Five percent of the population? Ten percent? Twenty percent? And just how poor are they?

– Who are you?

– I’m Mooney Kaufman. I’m the great-uncle of the brissee. So, where were we, Jerry? Jewish poverty in Israel?

– I’ll start talking about Jewish poverty there when we start talking about poverty here.

– We’ve already talked about Jewish poverty here.

– Poverty in Israel is nothing like the poverty here, believe me.

– Really? said Mooney.

– There are things there that are more important than money.

– For instance?

– Spirituality.

– Does it not cost money to be a member of this fine synagogue?

– Or love.

– If I go to a hooker she’ll charge me fifty dollars. Even one horrendously fat or horrendously thin. And if you want a partouse, then you’re looking at, what, a hundred twenty-five an hour? And that’s your de minimis.

– That’s not the kind of love I had in mind.

– A guy your age, I’m sure it’s the only kind of love you have in mind.

– Love of country, of your people, or for a child.

– How much do you think it costs to circumcise a child? I’d say five hundred dollars for a decent trim, maybe less for what they call a ‘French cut’.

– What’s a French cut?

– Half a circumcision, leaving a bit of the foreskin so as not to cut back on pleasure. Thoughtful parents.

– Gross, said Rachel.

– And let’s say four thousand for the kiddush — and that’s my de minimis. And how much do you think it cost your parents to raise you to the age of eighteen, not counting the T-shirt?

– How much?

– I’m asking you, Jerry.

– I don’t know.

– Guess.

– Can’t say.

– Rachel?

– You mean allowance?

– I’m talking room and board, the accumulated per diems of eighteen years, excluding loss of opportunity and lucro cesante. Anyone? I’d say — grosso modo — two hundred thousand.

– Big bucks.

– Almost a student loan.

– So what else is free that doesn’t cost money? asked Mooney.

– Your health?

– Ha!

– With medicare, you can see any doctor you want.

– Even Dr. Smirnoff?

– Who?

– Dr. Smirnoff.

Mooney made him clink glasses. The girls giggled. He had the others pour themselves healthy shots, raise them, and toast Dr. Smirnoff.

– To Dr. Smirnoff.

– To Dr. Smirnoff.

They all drank.

– That one didn’t count.

– You didn’t look each other in the eyes when you toasted.

The vodka flowed again.

– To the bagel!

– To bagels!

He was going to get these kids seriously drunk.

Two toasts later, Mooney rose. He was drunk, and he felt like he was walking on a rowboat. He cautiously shuffled to a long table with the coffee and pastry and stood in line. The table had been meticulously set, with a long single white damask cloth and more carnations, lines of cups and saucers arranged as straight as soldiers, several elegant thermoses polished to the sheen of surgical instruments, alongside his mother’s antique silver samovar for tea. Dave always took it to events like these.

Why did he get the samovar? That was irksome.

And there were equally burnished creamers and sugar bowls bursting with gourmet sugars and pink sachets of chemical sweeteners. There were cheesecakes and tortes, a magnificent sponge cake, mandelbrot, honey-cake, and rugelach, and frosted nothings, which he had liked as a kid.

I am the poorest Jew in America, Mooney thought, looking at the plenty. And at my age. Even the youngsters here are richer than me. That T-shirt probably cost more money that what I’ve got in my pocket after paying the pharmacist. He crunched a rugelach, the cheese dough so unmistakable.

He took his coffee cup and saucer and shuffled back to the table and set the saucer down carefully beside his plate without spilling, and without sitting down he sipped from the cup.

He leered at his venal brother Dave, who had once made a million dollars in a single day, rumour had it. They had still not exchanged a word, not even a hello-how-are-you, since Mooney arrived. With his mental powers he willed Dave to look at him.

Dave glanced back over his shoulder and saw Mooney sipping his coffee. He hadn’t been sure Mooney would come. Why had he invited him? Grief comes from goodness, he thought. Mooney disturbed his peace of mind, almost as much as that swift ritual mutilation of his grandson he had just witnessed. He was all smiles of relief now, but there had been a moment when the knife was lifted off the table ...

... and now that cunt Mooney. For a second they looked at each other. Dave waited for a nod, but nothing came out of his brother’s face. What a sucker punch.

His brother might cause trouble, as he did at his son’s wedding years ago, drunk on his vodka, before he was hospitalised. He nodded again to Mooney and numbly waited to see whether Mooney would nod back or cause a scene. Nothing. Another sucker punch.

Mooney sipped his coffee and stared into Dave’s nod. He had wished his wish. His mental powers had made Dave look at him and he snubbed him good. Tinkering with his teaspoon, he treated Dave to a large serving of Silence, as was always the case at these public family affairs where his invitation was compulsory, while to a private do there was never an invite, never a call, by far the bigger snub. Oh, how cruelty begins at home.

His presence was a sign to the community of his brother’s generosity for including the family derelict. But Mooney’s answer to that was Silence, and to spit on his brother’s Money, which he made in speculation, first at home and now around the world: buying up slum housing, so the standard slur against Dave went.

Dave and his varnished nails, surrounded by genuflecting friends. But they were satisfied looking, Dave’s friends, and they all seemed to fit. And the most satisfied looking of all was Dave. His fortune would go on increasing, even after death, thought Mooney, which was a really depressing thought.

Mooney couldn’t see Candy though, or his son and daughter-in-law, or the little brissee. They must have gone off on a family huddle to calm the kid. Fucking barbarians.

After waiting for the nod that never came from his brother, Dave turned and re-engaged his small group of guests. He was really irked. Mooney had got under his skin, again. And he cursed himself for having invited him.

Mooney sat down again. He poured himself a shot of vodka, which he drank in one gulp, still parched. The vodka tears soaked his eyelashes. For a moment no one noticed him, and for that it was like being back in the insane asylum, but with much better food, and without the hounding of the nurses to get him out of bed. And now his belly was full. A great nosh. In his welfare apartment now it was always a choice between hunger and bad food, but this was great food, even if he did feel like a moocher. He broke off some bagel, chewed and swallowed.

– Do they serve breakfast like this every Sunday? posing the question not to Jerry, but to the other young man on the other side of him, who had taken relish in certain parts of his conversation with Jerry.

– After services. Even though this is a private affair, the real Jews get that table over there. At the back.

– The shnorrer table, said the girl beside Rachel.

The kids giggled and pointed to the table with the real Jews.

– That’s the shnorrer table? asked Mooney. For the moochers?

– That’s what they call it, Rachel said. I think it’s mean.

– So can anyone come in and eat here every Sunday?

– You have to participate in the service.

– How long is the service now?

– Several hours, I think.

– They get here at sunrise. Bummer.

The shnorrer table. Now that was an expression. It brought back the old disgust he felt when he had first heard it uttered. Still, if he just sat through a service, he could eat here on Sundays, maybe even take home leftovers.

– What’s your name? Do I know you?

– Michael.

– You must be Susie Birnbaum’s boy?

– That’s right.

– What are you studying, Michael?

– Physics.

– That’s great, Michael. Do you know what your name means in Hebrew?

– No.

– Micha in Hebrew means ‘as’ or ‘like’, and –el means God. Like-God.

Unlike the young Jerry, this Michael had very short hair, which was peroxided yellow, and he was shaved up to his eyeballs. He wore a red Rage Against The Machine T-shirt that had a silk-screen of a confident el Che in short hair and burns without the beret.

– And you? Are you thinking of making aliyah?

– Me?

Everyone at the table laughed.

– Michael’s a self-hater, said Jerry.

– Sometimes he hates the fact he was born a Jew, someone said.

– Actually, sometimes I hate the fact that I was born altogether. And some of you.

The kids giggled.

– He hates himself because Rachel dumped him, said the girl on Rachel’s right. On his birthday.

Both Rachel and Michael blushed. Everyone else screamed with laughter. Between screams darts of commentary flew.

– I didn’t know it was his birthday!

– Yes, you did.

– I forgot.

– You like so did know.

– Nobody breaks up with anyone on their birthday.

– Rachel did.

– Would you please stop, please?

– Now she’s going out with Jerry, one of the other cousins reported.

– It happened a long time ago, said Rachel.

– Three weeks!

– But he’s still so in love with you, Rachel.

– He so isn’t, said Rachel.

– Yes, he is. Look at him.

Michael’s face was bright red. Mooney poured himself and Michael a shot of vodka and they drank, which eased the tension.

– Have you ever been to Israel? Mooney asked, checking to see if Jerry was listening.

– Once. Years ago. On my bar-mitzvah trip.

– Did you enjoy yourself?

– It opened my eyes.

– What more can you expect from travelling? Mooney said philosophically, to Michael.

– Yes, what more.

– Would you ever think of going back?

Everyone at the table turned to look, waiting on Michael’s answer.

– Me?

– Yes, you.

– He’s a self-hater. Why would he go back? asked Jerry.

– I’m asking Michael. Michael?

– I’d rather not answer that question.

– His mother’s here, one of the cousins said.

– You don’t have to answer me.

– I can’t answer you.

– Answer him, said Jerry.

– He can’t answer you, said Rachel. He’s promised his mother he would never discuss the subject in public.

– What subject?

– The thing.

– What thing?

– The thing. The thing he can’t talk about.

– Is that so, Michael?

– She has a bad heart.

– I don’t think she’d hear you.

– There are certain things you just can’t discuss in public, Michael said.

– We’re amongst friends, said Mooney. This is private. Would you, Michael?

– Would I what?

– Would you go back to Israel? Would you, Michael?

– I told you, I can’t talk about it.

– About what?

– About Israel if my mother’s around. Or if there are Jews in the room.

This broke everyone up. One of the Michaels girls pissed herself laughing.

– Imagine there were no Jews in the room.

– It’s a fucking briss.

– Just between you and me.

Jerry strained forward while the table held its collective breath. Michael blushed, about to talk. Mooney felt the ferocious heat. Michael’s silence was a black hole that seemed to suck in the kiddush din. Jerry narrowed his eyes as Michael opened his mouth with restrained passion.

– I can’t watch this, Rachel said. I’m covering my eyes.

– The only way I’d go back to Israel, Michael said, staring at Jerry, would be in a Hezbollah minivan.

– He said it! one of the cousins screamed.

The table broke up with laughter. Michael’s blush was now violet.

– What kind of Jew are you? said Jerry.

– Go tell his mother, someone snorted.

– The best kind. The moral minority.

– If we are not for ourselves, said Jerry.

– Ourselves? Who are we, anyway? The Jewish identity is just an invention. An invention of Christians and nineteenth-century German Zionists.

– Here we go.

– We Ashkenazim are descended from Khazars!

– You’re the chazzer!

– The Khazars were a Turkic people, Mongolians who loved to ride horses and plunder villages, who founded the first Kaganate and were converted to Judaism by Abrahamic Byzantines in the eighth and ninth century. Read Shlomo Sand.

– Read the Torah.

– We Ashkenazi Jews were never in Israel! It’s not our homeland. We’re Mongols.

All the kids broke up.

– You’re the mongoloid! Or at least your brother is!

This didn’t get such a laugh.

– And you’re an asshole.

– And you’re such a bullshitter.

– We’re really Khazars.

– Bullshit, bullshit, said Jerry.

– The Khazars/Jews were later pushed out by the Kievan Rus and eventually pushed west by the Mongol Golden Horde into Germany, where we began to speak middle-high German, which we call Yiddish.

– Bullshit, bullshit.

– If we have to return somewhere it would be to some place between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. The Pontic Steppe. To Kazakhstan or maybe all the way back to Mongolia.

– Bullshit, bullshit.

– We never came from Israel. The only people with real Jewish DNA are the Palestinians.

– Bullshit, bullshit.

– So you see, I’m not the self-hating Jew, you’re the self-hating Khazar who is in denial about being a Khazar. You’re the self-hater, Jerry.

Everyone was in stitches but Jerry, who stood up.

– Me? Because I don’t ride a horse? You’re such a bullshitter.

– Read Shlomo Sand.

– Bullshitter.

– And stop calling me a bullshitter.

Michael stood up, too.

– You are one. You are a bullshitter.

– Stop calling me a bullshitter, he said, leaning across Mooney, poking Jerry in the chest twice with his shot glass, once for bull and once for shitter.

Jerry didn’t like being poked in the chest.

– Don’t poke me.

– Why don’t you make aliyah to Kazakhstan? Just leave Palestine to the Palestinians and the Israelis. What’s it your business? You’re just a Khazar in denial. He poked Jerry in the chest again with his shot glass.

– You’re the chazzer.

– Don’t call me a chazzer.

– You prefer bullshitter? And stop poking me.

– Poking’s just a start, you piece of crap.

Mooney waved his napkin limply like a flag of truce, and checked to see if his brother Dave had noticed the commotion. His brother Dave did notice, interrupted his schmoozing and shot an irritated glance at him. This glance he returned with a nod.

He had created this mischief, Mooney realized.

– Stop poking me, said Jerry.

– What if I don’t?

Jerry threw what was left of his coffee at Michael, which missed him but drenched the girl sitting beside him. Michael laughed and so Jerry threw the empty cup, which hit Michael flush on the nose bone, from which blood flowed like the Nile. Michael wiped his nose, which kept bleeding, and threw his cup and contents wildly, hitting the kid beside Rachel on the forehead, who reacted by hoisting himself up by pushing down on the table board, which upended. Plates and cutlery were catapulted into the air and crashed onto other tables, even as far as the shnorrer table.

The two boys started to brawl, but not before Jerry got in a good punch. A tooth flew and they fell to the floor. Dave rushed over livid, collared Mooney and dragged him to the back of the room by the shnorrer table, leaving parents and kids to sort out the fight.

– Well, it’s obvious you shouldn’t have sat me at the kids’ table. Why didn’t you sit me with your rich friends? You should have sat me at least with the divorced wives.

– I should have sat you at the schnorrer’s table.

The shnorrer table took offence. Dave pulled Mooney even farther to the back of the room.

– I shouldn’t even have invited you.

– Why is the heat up so high?

– And you weren’t supposed to come.

– I brought your daughter-in-law bagels. For good luck.

– Leave the bagels and fuck off out of here.

– Actually, I came because I wanted to talk to you.

– About what?

– About the only thing you know anything about.

– I’m not giving you any more money.

– I need my money.

– Your eyelashes are so thick, he said to Mooney.

– It’s the Xalatan. I’m taking it for the glaucoma.

– You don’t have glaucoma.

– Yes, I do.

– You’re too young to have glaucoma.

– I was diagnosed.

– This was supposed to be a happy day for me.

He had to do it now. Ask his brother. In a minute it would be too late.

– I need money, said Mooney. I need the money you stole from me.

– I didn’t steal money from you. I’ve been giving you money for years.

– Dad says you did.

– Dad’s been dead for twenty years.

– He came to me in a dream. Told me what you did. He told me you stole my part of the inheritance.

– The fuck I did, Hamlet.

– He told me you stole my part of the inheritance.

– You’re nuts.

– You did it.

– Did what?

– Stole the inheritance.

– Why would I do that?

– You tell me.

– That would be admitting I did it. And I didn’t. How much money do you need?

– You mean how much do I want?

– Ok, how much do you want?

– Three million dollars.

– Right, three million dollars.

– The money you stole from me.

– I didn’t steal any money from you. I’ve been giving you money for years.

– You stole it.

– This is ridiculous. I have to get back to my guests.

– They’re all leaving.

– Thanks to you.

Dave looked at Mooney. Suddenly it hit him that he would always have the same brother for the rest of his life.

– I’m living on welfare. You don’t know what that’s like.

– I know enough about it not to want to live on welfare.

– You don’t know what it’s like!

– What’s it like?

– It’s like —

– Don’t answer. Just fuck off out of here.

– It’s like being seated at the shnorrer table for eternity, said Mooney. Tell me, by what right are you keeping my money? The right of theft?

– The inheritance was settled years ago. You blew yours.

– Hey, that kid lost a tooth.

– Look, Ma’s coming over. Don’t upset her.

He hadn’t noticed she was even there, and now she was hobbling over, brushing cake crumbs off her bosoms. The doctors at the hospital had told her not to get too close to Mooney, that she was somehow an impediment to his recovery. Them and their two-bit psychology.

– Ma.

– Mooney.

– I thought you weren’t supposed to talk to me.

– I’ll talk to who I want. Smartass doctors. Someday they’ll learn.

– Ma, what have you done to your hair?

– I had it permed.

– It looks awful, said Dave.

– Dave, let go of your brother.

– Thank you.

– You, I don’t like the way you look. Are you sick?

It dawned on them then that Dave had had Mooney in a headlock since they arrived at the schnorrer table.

– I don’t want you two fighting. He’s sick, Dave.

– It’s always about him, isn’t it?

– Before I die I want you two to get along.

– You’re not going to die, said Mooney.

– Is it that bad? Mrs. Kaufman asked.

– What?

– My perm.

– You look great, Ma, said Mooney.

– You look like a woman who plays bingo at a Ukrainian church, said Dave.

Mrs. Kaufman didn’t find that funny.

– I want you both to come for supper tomorrow.

– Can I bring my dog?

– No dogs and no wives. You’re eating my heart out, you two.

– I’m busy tomorrow, said Dave.

– You’ll be there.

– The fuck I will.

– And you too, Mooney.

– What are you making?

– I was thinking delicatessen. Dave, you pick it up.

– The fuck I will.

– No fat on the corned beef.

– You’ve got crumbs on your front, Ma, said Dave.

– I have?

– I can’t make it tomorrow night, said Dave.

– Lean corned beef.

– You should brush off the crumbs, Ma.

– What crumbs?

– On your front.

– Have I got crumbs, Mooney?

– Yes, but they’re invisible, he replied.

|