| FindBook |

有 2 項符合

敕勒人的東遷(國際英文版)的圖書 |

|

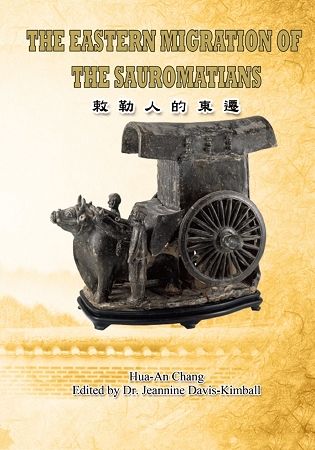

敕勒人的東遷(國際英文版) 作者:常華安 出版社:漢世紀數位文化EHGBooks 出版日期:2017-11-01 規格:22.8cm*15.2cm (高/寬) / 平裝 / 370頁 |

| 圖書館借閱 |

| 國家圖書館 | 全國圖書書目資訊網 | 國立公共資訊圖書館 | 電子書服務平台 | MetaCat 跨館整合查詢 |

| 臺北市立圖書館 | 新北市立圖書館 | 基隆市公共圖書館 | 桃園市立圖書館 | 新竹縣公共圖書館 |

| 苗栗縣立圖書館 | 臺中市立圖書館 | 彰化縣公共圖書館 | 南投縣文化局 | 雲林縣公共圖書館 |

| 嘉義縣圖書館 | 臺南市立圖書館 | 高雄市立圖書館 | 屏東縣公共圖書館 | 宜蘭縣公共圖書館 |

| 花蓮縣文化局 | 臺東縣文化處 |

|

|

- 圖書簡介

From the time of the "Chaos of the Eight Princes" (291 IV. Modern Western Literatures) in the Western Jin Dynasty, China suffered from civil strife and foreign aggression. After nearly three hundred years the people lived in extreme poverty until Emperor Wen of the Sui Dynasty unified China in 589 CE. The continual strife had created a melting pot and laid the foundation for the subsequent Sui and Tang Dynasties.

Among the many ranks of barbarians that migrated into China, one nomadic tribe - the Sau-ro - has been ignored by classical historians. The correct pronunciation of "敕勒" is "Sau-ro," which is a shortened form of the translated word Sauromatae. Sauromatae is the name of their western homeland, probably modern-day Ukraine. During the mid-4th century, the Sau-ro nomads fled because of a great famine that had overtaken their homeland. They nomadized this great distance to Siberia and Mongolia searching for water and fodder for their flocks. Over time their migration continued, this time toward the south in quest of a more hospitable climate. As to be expected, local nomads with superior mobility and combat effectiveness attacked them along the way. The Sau-ro thus suffered defeat in 399 CE and again in 429 CE. Following these vanquishments the Northern Wei took approximately half-a-million Sau-ros, who had settled in central Mongolia and Trans-Baikal, prisoner. They were then again re-settled on the steppes of Inner Mongolia.

Around 430 CE, approximately another half-a-million Sau-ro, who had now occupid southern and western Siberia, were placed into servitude by the Rou-ran. In 487 CE, the Sau-ro migrated to northern Xinjiang where they established an empire that the Chinese designated Ko-ch. Bad luck was again to strike the Ko-ch people of the Sau-ro Empire for in 551 CE the Tu-jue ambushed and conquered them in Xinjiang Province. The Sau-ro Empire was now decimated. In 630 CE the remaining Ko-ch were re-settled in the Ordos. This filled a void as the Tang Dynasty had annihilated the former inhabitants, the Eastern Tu-jue. Because of heavy taxation and hard labor, the Ko-ch rebelled twice, once in 721 CE and again in 722 CE. Following the suppression of the 722 CE insurrections, the remaining slightly more than 50,000 Sau-ros were then re-settled as farmers in southern Henan Province.

Previously, in 429 CE many Sau-ro had been relocated to the "Six Garrisons" in Inner Mongolia. By 525 CE bureaucratic corruptions had become so oppressive that riots broke out and many Sau-ro were included among the rioters. Because of their loyalty, bravery, wild disposition, and skilled martial arts, a number of Sau-ro emerged, as founding fathers while other became high-ranking officers of the Eastern Wei and Western Wei Dynasties. When they entered China the necessity to comply with the compulsory Chinese Han culture forced the Sau-ro to conceal their identities. They integrated into the Chinese Han culture, took Chinese surnames, and intermarried with the Chinese.

Today, fourteen hundred years later, after erroneous and incomplete historical records since the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE), the descendants of the Sau-ro know little of their ancestry. They do not know the correct pronunciation of their tribal name, or even less of the contributions their progenitors had infused into Chinese culture. The historical documents of the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), which may have been manipulated by political forces, considered the Sau-ro to be the Ding-ling or Tie-le people. Historical researchers, studying the documents compiled between 429 CE and 551 CE, have been unable determine the real identies of the many tribal groups. Even the master historian Chen Yin-ke (陳寅恪) was not able to solve this enigma. As this confusion occurred more than a millennia ago, we must now augment the ancient texts with data from archaeological excavations and western research in hopes of finding the missing links in the Chinese historical records.

Since the mid-19th century, Russian and Chinese archaeologists have excavated an enormous quantity of burials and their artifacts in Siberia, Trans-Baikal, Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, Manchuria, and Xinjiang. These have been stylistically identified as Scytho-Sarmatian and as the product of Sarmatian tribes. These archaeological remains are valuable resources that augment inadequate Chinese literature and also serve as a guide to trace the tribal migrations.

In researching the Scytho-Sarmatian burials and artifacts, both Chinese and western archaeologists have relied on C14 dating. This type of dating is problematic as often artifacts belonging to the great grandson are mistaken for those belonging to the great grandfather. This results in artifacts that are labled Xiong-nu in fact do not belong to the Xiong-nu nor Ding-ling nor Tie-le culture.

The eastward migration of Sauromatian is an important chapter in the expansion of the western culture into eastern Asia. Westerners have not known where the Sauromatians went after they mysteriously disappeared from the Ukraine steppes in the mid-4th century CE. Neither did the Chinese know where they had come from. Emperor Tai-zong and his son, Emperor Gao-zong, of the Tang Dynasty further deliberately misled by the Chinese into believing that they were the Siberia aboriginal Ding-ling or Tie-le (Oghuz).

Thus, this important chapter of West-East cultural exchange and the significant impact the Sauromatians had upon the eastern Asian populations has not been recognized. The development of power by the Northern Wei Empire, and the establishment of both Eastern Wei and Western Wei regimes were all marked by the hardships suffered by the Sauromatians. Obscure oriental nomads, such as Rou-ran and Turks, enjoyed a sudden surge of power after they had annexed the Sauromatian tribes, and were relatively able to quickly establish their own empires.

The biggest impact the Sauromatians introduced to the oriental nomads was their Runic alphabet and their heavy combat cavalry. To the Han Chinese, however, the biggest Sauromatian contribution was neither heavy cavalry nor the Runic alphabet nor Scytho-Sauromatian portable art but a limited number of outstanding Chineselized political and military leaders. These people of Sauromatian descent were among the important founding monarchs of Sui and Tang dynasties and under their leadership an age of prosperity ruled over China. Although their grandfathers and fathers were once prisoner of war, these people were able to accomplish an outstanding military career from grassroots. They gradually attained the prestigious position of either a high-ranking officer or founding father. Later generations under the patronage of elders established new dynasties without employing a similar ethnic military force. These accomplishments are remarkable when compared to other armed barbarians who established regimes in China including the Wu-hu (Five Barbarians), Khitan, Jurchen, Mongolian, and Manchu. The principal difference was that Sauromatians had become Chineselized before they establish their own dynasties, so that the nature of their regime was Han Chinese, not barbarian.

As Historian Master Chen Yin-ke said, "The reason the Li-Tang clan was able to rise suddenly is because of their infusion of the strong and unyielding barbaric blood from Northern barbarians into the decaying body of Chinese culture. Once the old vulgar custom was abolished, a new spirit grew, and an unprecedented world naturally emerged." Because the royal families of the Sui and Tang Dynasties had barbarian blood, China was able to establish a civil examination system to replace the system of selection from powerful families. Since then, this examination system has changed all the classes of the society for over a thousand years. It was truly a turning point for the social classes in China." - 作者簡介

The author was born in Cheng-du city, Si-chuan Province, China in 1945 after World War II. His family moved to Taiwan from Beijing in 1948. He graduated from the Department of Law of National Taiwan University in 1967 and Master of Jurisprudence of Howard Law School (without diploma) in Washington D.C. in 1980.

Mr. Chang is known as the only researcher in Sauromatians in Taiwan and China, he is also the author of The Eastward Migration of Sauromatians etc. in 3 diferent Chinese editions. This English edition was kindly edited and reviewed by the famous outstanding archaeologist Dr. Jeannine Davis-Kimball. - 目次

Contents

Acknowledgements

About Author

Contents

Preface

Forward

Misidentification

Chapter One. Nomadic Peoples in Northern China: Classification and Discussion

Section 1. Ding-ling, Sau-ro, Ko-ch, and Tie-le

Section 2. The Origin of the Name “Koch”

Section 3. Is Ko-ch Ding-ling (Dian-len)?

Section 4. The Ethnic Origins of the Northern Chinese Nomads

Section 5. Are the Di-li, the Sau-ro, and the Ding-ling the Same People under Different Transliterations?

Section 6. Is the Sau-ro the Tie-le?

Chapter Two. The Origin of the Sauromatians and their Westward Migratation

Section 1. The Place of Origin of the Sauromatians

Section 2. The Sauromatians in Europe

III. The Ugri and the Royal Scythian Tribes

Chapter Three. The Eastward Migration of the Sauromatians

Section 1. The Reasons the Sauromatians Left the Ukrainian Steppes

Section 2. Evidence of Sauromatians Arrival in Eastern Asia

Section 3. The Eastward Migration of Sauromatians

The estimated time the Sauromatians left the Ukrainian Steppes is as follows: if the Bosporus Kingdom perished in 341 CE, and the Huns crossed the Volga River ca. 350 CE, then the time allocated for the Sauromatians to leave the Ukrainian steppes would be between these dates or between 341 and 350 CE.

The estimated time of their arrival in eastern Asia is as follows: the appellation Sau-ro first appeared in a Chinese chronicle was July 357 CE. We therefore deduce that Sauromatians arrived in Siberia between 350 CE and 355 CE, and the arrival time in Minusinsk and Mongolia should be slightly later.

Section 4. The Relationship between Alani and Sauromatians

Chapter Four. The Ko-chs

Section 1. Sarmatae or Sauromatae?

Section 2. The Sau-ro State in Kasgar, Xinjiang

Section 3. Behaviors and Characteristics

Section 4. Religious Beliefs and Worships

Section 5. Marriage and Burial Customs

Section 6. Attitude towards Widows

Section 7. Physiognomy

Section 8. Is Emperor Tang Tai-zong (Li Shi-min) a Ko-ch Descendant?

Section 9. Horses and Heavy Cavalry

Section 10. Carriages

Chapter Five. The Early Stage of Sauromatians in Asia(350 CE to September 429 CE)

Section 1. The Relationship between Sauromations and the Asian Nomadic Minorities

Section 2. The Relationship between the Sauromatians and the Powerful Xian-bei

I. Attacks Launched by the Murong Xianbei

II. Attacks Launched by Tuoba Xianbei (Figure 36)

III. The Ko-ch Relationship with the Rou-ran

Section 3. The Rou-ran, Avar and Pseudo-Avar

Section 4. The Ko-ch Tribes in the Northern Wei Court

Section 5. Is Feng-lin Castle the Royal Castle of the Rou-ran (Tar–tar)?

Section 6. Are the Saka the Asian Scythian?

Chapter Six. The Sauromatian Tribes under the Reign of the Northern Wei (429 CE to 581CE)

Section 1. Cultivation and Grazing in Inner Mongolia (429-523 CE)

Section 2. The Exodus of Sauromations from the Northern Wei

Section 3. The Six Garrisons Riot and the Establishment of the Eastern Wei and the Western Wei (523-581 CE)

Section 4. The Number of Bronze Age Cultures Found at Yinxu and the Identity of the Caucasoid Skulls

Section 5. Castle Ruins in Mongolia and the Trans-Baikal

Section 6. Abakan Han-style Palace

Section 7. The Y Chromosome Haplogroup of the Sauromatians

Chapter Seven. The Sauromatian Tribes in Southern and Western Siberia (October 429 to 722 CE)

Section 1. Rule under Rou-ran (430-487 CE)

Section 2. The Migration to Dzungaria and the Establishment of the Ko-ch Empire (487 CE to 551 CE)

A. The Demise of Qiong-qi’s Branch and the Treasure of Tillya-tepe

B. The Death of A-fu-zhi-luo and the Succession of Mi-e-tu

C. The Death of Mi-e-tu

D. The Incessant Infighting between Ko-ch and Rou-ran and the Rise of Tu-jue

E. Why the Ko-ch Empire Never Attacked the Turks

Section 3. Errors in Chinese Chronicles

Section 4. Rule under Tu-jue (551-630 CE)

Section 5. Six-Hu State Period (630-722 CE)

C. Establishment of the Kuang and Chang States and the Lan-chu Commanding General’s Office (704-722 CE)

Section 6. Language and Alphabets of the Sauromatians

A. Spoken Language

B. Alphabets

B. The Relationship between Sauromatians, Goths, and Turks

Section 7. Cooking Cauldrons and Their Makers

Section 8. Blond, Shi-wei, Mucri, and Jurchen

A. Blond Shi-wei and Jurchen

B. The Blond Mucri

Section 9. The Iron Age in Southern Siberia

Section 10. Slab Graves

Section 11. The Origin of Hephthalites

Chapter Eight. Dating the Scytho-Sauromatian Artifacts From Eastern Asia

Section 1. Archaeological Results

I. Western Archaeological Results

II. Chinese Archaeological Results

Section 2. Problems of C14 Dating

Section 3. Calibrating Carbon Dating by Dendrochronology

Section 4. Dating by Typology

Section 5. The Relationship between Scythian and Sauromatian

C. Is the Father of Emperor Wen of the Sui Dynasty, a Scythian?

Genetic Ties between Scythians and Sauromatians

The Integration of Scythian and Sauromatian Art

Section 6. Xiong-nu Art

Section 7. Dating Eastern Asian Scytho-Sauromatian Artifacts

Arzhan-1 and Arzhan-2 Kurgans, Tuva Republic

The current dating is between the 8th and 7th century BCE.

Summation

Bibliography

|