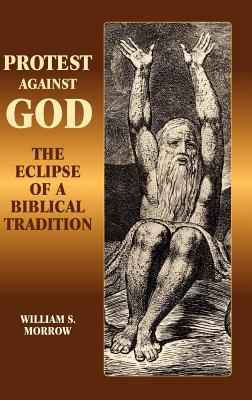

The Hebrew Bible contains many examples of protest or complaint against God. There are classic cases in the psalms of individual lament, but we find the same attitude in community complaint psalms, in the prophetic challenges to God, and in the Book of Job. And yet, after the exile, the complaint tradition was largely suppressed or marginalized. In this imaginative book, Morrow asks the unheard of question, Why? A shift in the religious imagination of early Judaism had taken place, he argues, spearheaded by the psychology of trauma and by international politics. A magnification of divine transcendence downgraded the intercessory role of the prophet, controlled the raw pain of exile (Lamentations, Second Isaiah), and led to intransigent refusal of the logic of lament (the friends and Yahweh in Job). The theology of complaint was eventually overshadowed by the piety of penitence and praise (the Dead Sea Scrolls). Modern readers of the Hebrew Bible are not obliged to assent to the loss of lament, nevertheless. Ours is an age when the potency of the biblical complaints against God is being newly appropriated. Although the transcendental imagination of Western culture itself is moving into eclipse, a heightened individual consciousness has emerged. There may still be life, therefore, in the ancient prayer pattern of arguing with God, which assumes that worshippers have rights with God as well as duties, that the Creator has obligations to the creation as well as prerogatives. This stylish intellectual history will be welcomed for its scope, its panache and its theological engagement.

| FindBook |

有 1 項符合

Protest Against God的圖書 |

|

Protest Against God 作者:Morrow 出版社:Sheffield Phoenix Press Ltd 出版日期:2006-08-17 語言:英文 規格:精裝 / 264頁 / 23.4 x 15.5 x 1.5 cm / 普通級 |

| 圖書館借閱 |

| 國家圖書館 | 全國圖書書目資訊網 | 國立公共資訊圖書館 | 電子書服務平台 | MetaCat 跨館整合查詢 |

| 臺北市立圖書館 | 新北市立圖書館 | 基隆市公共圖書館 | 桃園市立圖書館 | 新竹縣公共圖書館 |

| 苗栗縣立圖書館 | 臺中市立圖書館 | 彰化縣公共圖書館 | 南投縣文化局 | 雲林縣公共圖書館 |

| 嘉義縣圖書館 | 臺南市立圖書館 | 高雄市立圖書館 | 屏東縣公共圖書館 | 宜蘭縣公共圖書館 |

| 花蓮縣文化局 | 臺東縣文化處 |

|

|

圖書介紹 - 資料來源:博客來 評分:

Protest Against God 相關搜尋

The Translation of Holy Quran (聖クルアーン) Japanese Languange Edition UltimateMother of Invention: Mother Teresa and the Franciscan Servants of Jesus

Is EVOLUTION True?: Why Darwin’s Rejection of Intelligent Design no longer makes sense. Why Life really is a miracle in the true sense

Systematic Theology (Volume 3)

A System of Logic: Ratiocinative and Inductive, 7th Edition, Volume. II

The Syrian Christ

Christianity as Mystical Fact, and the Mysteries of Antiquity

Christmas Evans, the Preacher of Wild Wales; His country, his times, and his contemporaries

Bible Myths and their Parallels in other Religions; Being a Comparison of the Old and New Testament Myths and Miracles with those of the Heathen Natio

Dismantled: Abusive Church Culture and the Clergy Women Who Leave

|