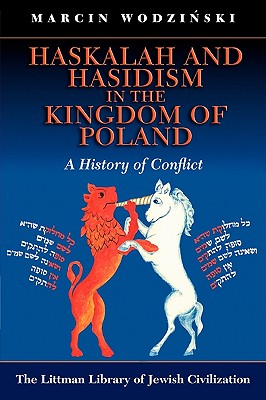

The conflict between Haskalah and hasidism was one of the most important forces in shaping the world of Polish Jewry for almost two centuries, but our understanding of it has long been dominated by theories based on stereotypes rather than detailed analysis of the available sources. In this award-winning study, Marcin Wodziński challenges the long-established theories about the conflict by contextualizing it, principally in the Kingdom of Poland but also with regard to other parts of eastern Europe. Covering the period from the earliest anti-hasidic polemics in the late eighteenth century through to the post-Haskalah movements of the twentieth century, it follows the development of this important conflict in its central arena.

Using source materials (including many hitherto unknown documents) in Polish and five other languages, Wodziński has succeeded in reconstructing the way the conflict expressed itself. Identifying the motives, the methods, and the consequences of the conflict as it was played out in five Polish towns (Lódz, Opoczno, Piotrków, Warsaw, and Warta), he shows that it was primarily informed by non-ideological clashes at the level of local communities rather than by high-level ideological debates.

Much attention is also devoted to the general characteristics of hasidism and the Haskalah, as well as to the post-Haskalah movements. Here too Wodziński challenges the ideologically charged assumptions of a generation of historians who refused to see the advocates of Jewish modernity in nineteenth-century Poland as an integral part of the Haskalah movement. Extensive consideration is given to the professional, social, institutional, and ideological characteristics of the Polish Haskalah as well as to its geographic extent, and to the changes the movement underwent in the course of the nineteenth century. Similar attention is given to the influence of the specific characteristics of Polish hasidism on the shape of the conflict, especially as regard the size of the movement and the evolution of hasidic communal involvement. In consequence the book presents a synthesis that offers both breadth and depth, contextualizing its subject matter within the broader domains of the European Enlightenment and Polish culture, hasidism and rabbinic culture, tsarist policy and Polish history, not to mention the ins and outs of the Haskalah itself across Europe.

An extensive appendix presents translations of nineteen important and hitherto unknown sources of relevance to a nuanced understanding of many aspects of nineteenth-century Jewish history in Poland and eastern Europe more generally.