Populist parties in Europe attract many more votes than they did just a few decades ago and are now much more likely to govern. They have also become key players in the international sphere, especially in Europe. At the same time, the relationship between democracy and populism is subject to substantial scholarly and public debate. This raises questions about opposition to this controversial set of political actors: do opponents favour the use of rights-restricting and exclusionary repertoires typical of ’militant democracy’ responses to anti-democratic or extremist parties? Or do opponents favour the ordinary, persuasive and sometimes inclusive strategies more typical of the daily conduct of liberal democratic politics? To what extent is opposition conceived of as democratic defence? How do strategies vary among countries and in relation to different types of populist parties? How do international and transnational actors respond?

Addressing these questions, the book presents new research mapping opposition to the Hungarian Civic Alliance (Fidesz), Law and Justice in Poland, Alternative for Germany, League and Five Start Movement in Italy, Podemos and Vox in Spain, the Sweden Democrats and the Danish People’s Party. It argues that opposition to populist parties in contemporary Europe is, in most cases, best conceived of as democratic defence as normal politics. That is, while there is no direct link between populism and a decline in democratic quality, critical claims justifying acts of opposition often problematise populist parties as threats to liberal democratic principles and values. At the same time, political actors are more likely to oppose populist parties using the repertoires of normal politics - or strategies typically employed against less controversial groupings - than the exceptional, rights-restricting instruments they typically use against extremists. The case of Alternative for Germany, in which exceptional politics continues to guide much opposition, remains a case apart.

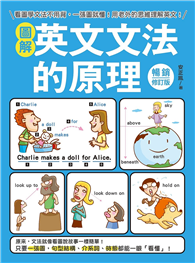

看圖書介紹

看圖書介紹