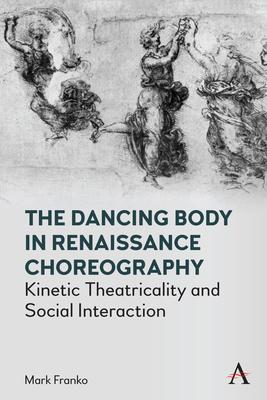

Renaissance dance treatises claim that the dance is a language but do not explain how or what dancing communicates. Since the body is the instrument of this hypothetical language, The Dancing Body in Renaissance Choreography problematizes the absence of the dancing body in treatises in order to reconstruct it through a series of intertextual readings triggered by Thoinot Arbeau’s definition of dance as a mute rhetoric in Orchesographie. This book shows that the oratorical model for Arbeau’s definition of the dance is epideictic and that although one cannot equate dance and oratorical action, the ends of oratorical action are those of dance: persuasion through charm and emotion.

The analysis of the rhetorical intertext opens the way to a sociological one. Through a reading of courtesy books as well as a chapter of Tuccaro’s L’Art de Sauter et Voltiger en l’air it is shown that dance and social behavior were not discontinuous in the Renaissance. Instructions for the body can be divided into the categories of the pose and movement. They are examined as a model for the most important and widely practiced dance of the Renaissance: the basse danse. The characteristic motion resides in an opposition as well as an interpenetration of stillness and mobility. This is developed through a reading of fifteenth-century dance theorists’ concept of misura and fantasmata. Stefano Guazzo’s La Civil Conversazione is used as a textual interpretant to ascertain the strategy of movement and the pose in the interaction between dancer and spectator.

看圖書介紹

看圖書介紹