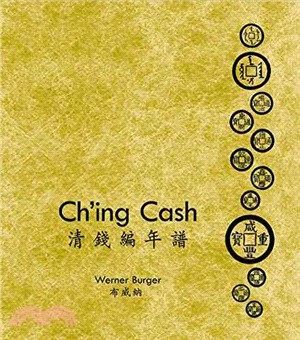

?Ch’ing Cash is a monumental two-volume set detailing the history of Ch’ing cash coins. The first volume lists the development of Ch’ing cash, its manufacture, and the stages from ivory trial pieces to final product. Werner Burger has developed a novel way for numismatics to present the coins, arranging each coin by individual mint and year produced, which has led to several unexpected discoveries. The second volume contains the rubbings of more than 6,000 coins in 53 large foldout charts. Each coin includes a rarity index and number. In addition, Burger has compiled a list of all coins cast by every mint from 1736 until 1911.

| FindBook |

|

有 1 項符合

Werner Burger的圖書 |

|

$ 21401 | Ch'ing Cash : Volume 1―Ch'ing Cash; Volume 2―Ch'ing Cash Year Tables

作者:Werner Burger(布威納) 出版社:香港大學美術博物館 出版日期:2016-03-01 規格: / 精裝 / 324頁  看圖書介紹 看圖書介紹

|

|

|

圖書介紹 - 資料來源:博客來 評分:

圖書名稱:Ch’ing Cash: Ch’ing Cash / Ch’ing Cash Year Tables

|