Fully annotated edition.

The two greatest masters of the art are François Baucher and James Fillis [Principles of Dressage and Equitation, a.k.a Breaking and Riding with full military commentaries, Xenophon Press 2017]. With them, in the light of their principles, riding has become truly an art, because these masters have been satisfied to set forth their practices, without giving the reason, the wherefore, of the acts which they dictate. For example, the two effects of the rider’s hand upon the lower jaw of the horse impel the animal to the right or to the left. The pressure of the rider’s legs upon the horse’s flanks gives two more sensations. Here, then, are four signs, by means of which the rider communicates with his mount and thereby controls its entire mechanism. These sensations, caused in a living animal, certainly have for it a meaning: they oblige certain parts to act. The rider closes his leg upon the horse’s right flank, and the horse turns to the right. But what is the mechanical reason?

When each and every movement of the horse in response to its rider’s signals is explained on mechanical principles, then equitation is no longer an art. It has become a science, and therefore invariable. The difference between my system of training the horse and the systems of Baucher and Fillis is, in part, that I have carried farther the science as distinguished from the art. But besides this, while Baucher and Fillis trained their horses for the sake of executing the movements of the high school, I employ these airs of the high school, not as an end in themselves, but as a means for developing the physical and mental qualities of the horse itself. These masters specially chose the animals which they were to train. I, by means of my system of gymnastics, seek to improve and develop an animal of any original conformation that may be given me.

The purposes of this manual are, therefore, to explain the mechanical reason for every effect which the rider exerts on the horse, and to set forth the successive steps by which, practically, an actual animal is to be trained and developed. Underlying principles and theories are everywhere explained with the greatest possible clearness. In spite of a good deal of inevitable condensation, the methods here set forth should prove perfectly easy both to understand and to apply.

For seventy-six years, as cavalier, as student, as instructor, I have ridden, under every sort of conditions, horses of every type, every conformation, and every breeding. My first experiment, at the age of five, was with a donkey, young and entirely unbroken. At the beginning, I was more often on the ground than on the donkey’s back; but after six months of perseverance, all its gambols failed to unseat me. At eight years, I had a pony, thirteen and a half hands high; and I received instruction from the Comte d’Aure, Esquire-in-Chief of the cavalry school."

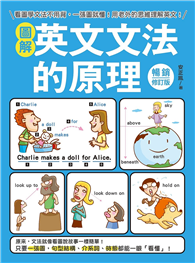

看圖書介紹

看圖書介紹