| FindBook |

|

有 1 項符合

Silas Waletofe的圖書 |

|

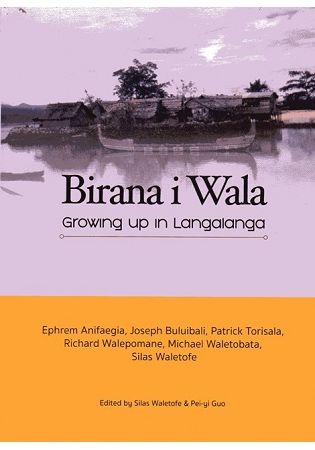

$ 405 ~ 450 | Birana i Wala Growing up in Langalanga

作者:Silas Waletofe、Pei-yi Guo 出版社:中央研究院民族學研究所 出版日期:2018-07-01 語言:繁體書  共 6 筆 → 查價格、看圖書介紹 共 6 筆 → 查價格、看圖書介紹

|

|

|

The Wala reside in the Langalanga Lagoon on the west coast of Malaita island, Solomon Islands. Written by local writers in collaboration with an academic researcher, the purpose of this book, Birana i Wala, is to preserve a written document of the fast disappearing Wala tradition (falafala/kastom) for the people of Wala and their future generations.

The book is divided into three major parts. Part One introduces Wala culture and society, including their history, kinship and social organization, religious beliefs, and social norms. Part Two illustrates daily life in the lagoon, in particular Wala heritage of shell money, fishing and canoe. Part Three explores the rites of passage in Wala lives, from birth, childhood, the teenage period, marriage to the end of life.

- 作者: Silas Waletofe、Pei-yi Guo

- 出版社: 中央研究院民族學研究所 出版日期:2018-07-01 ISBN/ISSN:9789860559620

- 語言:繁體中文 裝訂方式:軟精裝 頁數:421頁

- 類別: 中文書> 社會科學> 文化研究

|